| If we put our phones down, do we really become better readers—or simply different ones? | Khi chúng ta đặt điện thoại xuống, liệu chúng ta có thực sự trở thành những người đọc tốt hơn — hay chỉ là những người đọc theo cách khác? |

| In this article, the author reflects on a personal experiment of quitting social media to examine whether reduced screen time naturally leads to deeper reading habits, and uses this experience to question common fears about declining literacy, the changing meaning of reading in the digital age, and the uneasy trade-off between speed, specialization, community, and the slow, demanding pleasures of books. | Trong bài viết này, tác giả nhìn lại một thử nghiệm cá nhân: tạm rời xa mạng xã hội để xem liệu việc giảm thời gian nhìn màn hình có tự nhiên dẫn đến thói quen đọc sâu hơn hay không. Từ trải nghiệm đó, tác giả đặt lại những nỗi lo quen thuộc về sự sa sút của khả năng đọc, về ý nghĩa đang thay đổi của “đọc” trong thời đại số, và về sự đánh đổi đầy bất an giữa tốc độ, tính chuyên môn hóa, cảm giác cộng đồng với niềm vui chậm rãi, đòi hỏi kiên nhẫn mà sách mang lại. |

Illustration by thewordyhabitat

Minh họa bởi thewordyhabitat

| Original article (written in English) | Bản dịch của bài báo (sang tiếng Việt) |

| Here’s a thought many of us have these days: if only we weren’t on our damn phones all the time, we would surely unlock a better self—one that went on hikes and talked more with our children and felt less rank jealousy about other people’s successes. | Dạo này hẳn nhiều người trong chúng ta đều từng nghĩ thế này: giá mà mình không dán mắt vào cái điện thoại chết tiệt suốt ngày, thì chắc chắn sẽ mở khóa được một phiên bản tốt hơn của chính mình — một con người hay đi bộ đường dài hơn, trò chuyện với con cái nhiều hơn, và bớt cảm thấy ghen tị cay đắng trước thành công của người khác. |

| It’s a nice idea; once a day, at least, I wonder what my life would be like if I smashed my phone into bits and never contacted AppleCare. Would I become a scratch golfer or one of those fathers who does thousand-piece puzzles with his children? Would I direct ambitious films that capture the Zeitgeist? Would I at least read more difficult novels? | Đó là một ý tưởng khá dễ chịu; ít nhất mỗi ngày một lần, tôi lại tự hỏi cuộc sống của mình sẽ ra sao nếu tôi đập nát chiếc điện thoại và không bao giờ gọi cho AppleCare nữa. Liệu tôi có trở thành một tay golf hạng scratch, hay kiểu ông bố kiên nhẫn ngồi ghép những bức tranh ghép nghìn mảnh với con? Liệu tôi có đạo diễn được những bộ phim đầy tham vọng, nắm bắt được tinh thần thời đại? Hay ít nhất, tôi có đọc được những cuốn tiểu thuyết khó nhằn hơn không? |

| The unrest about smartphones and social-media addiction has been growing for years and shows no signs of abating. I have felt the panic myself, and so, this past July, with a book deadline looming, I got off of social media. The break started with X, which was my biggest problem, but, by the end of August or so, Instagram, TikTok, and pretty much anything that allowed me to argue with strangers had been deleted from my phone. Before this, I was spending roughly ten hours a day looking at my phone or sitting at my desktop computer. I didn’t need that number to come down, but, when I checked my weekly status report, I wanted all the brightly colored little bars that track the number of hours I’d spent on time-wasting apps to be relocated to the word-processing app that I use to write my books | Sự bất an xoay quanh điện thoại thông minh và chứng nghiện mạng xã hội đã âm ỉ nhiều năm nay và dường như chưa có dấu hiệu hạ nhiệt. Bản thân tôi cũng từng hoảng hốt vì điều đó, nên vào tháng Bảy vừa rồi, khi hạn chót cho một cuốn sách đang đến gần, tôi quyết định rời xa mạng xã hội. Cuộc “cai” bắt đầu với X — nền tảng khiến tôi sa đà nhất — nhưng đến khoảng cuối tháng Tám thì Instagram, TikTok, và hầu như mọi thứ cho phép tôi tranh cãi với người lạ đều đã bị xóa khỏi điện thoại. Trước đó, tôi dành chừng mười tiếng mỗi ngày để nhìn vào màn hình điện thoại hoặc ngồi trước máy tính để bàn. Tôi không nhất thiết phải giảm con số đó xuống, nhưng khi xem báo cáo sử dụng hằng tuần, tôi chỉ mong tất cả những cột màu sặc sỡ ghi lại số giờ lãng phí cho các ứng dụng vô bổ kia được “chuyển hộ khẩu” sang phần mềm soạn thảo văn bản mà tôi dùng để viết sách. |

| The plan worked, more or less. I finished a draft of the book on time. But the other imagined effects of a social-media detox never quite materialized, at least not in a noticeable way. I was especially hoping that I would start reading more books, because I have found that enviable prose prompts me to try to write my own, not necessarily out of a sense of inspiration but rather out of fear that if I don’t hurry up and start typing, I’ll fall behind. And yet, the chief effect, I found, was that I simply didn’t know what was happening in the world. That was nice enough, but all those books I had hoped to read never found their way into my hands. | Kế hoạch ấy nhìn chung là có hiệu quả. Tôi hoàn thành bản thảo đúng hạn. Nhưng những tác dụng khác mà tôi từng hình dung về việc “detox” mạng xã hội thì rốt cuộc lại không mấy xuất hiện, ít nhất là không rõ rệt. Tôi đặc biệt hy vọng mình sẽ đọc được nhiều sách hơn, bởi tôi nhận ra rằng văn chương hay thường thôi thúc tôi thử viết cho bằng được — không hẳn vì cảm hứng, mà vì nỗi sợ rằng nếu không nhanh tay gõ phím, tôi sẽ tụt lại phía sau. Thế nhưng, tác động lớn nhất mà tôi cảm nhận được lại là: tôi gần như không biết chuyện gì đang xảy ra trên thế giới. Điều đó cũng dễ chịu theo một cách nào đó, nhưng rốt cuộc, những cuốn sách tôi mong sẽ đọc vẫn chẳng tự nhiên tìm đến tay mình. |

| One of the more common doomsday scenarios about social media goes something like this: an internet-addicted public, hooked on the dopamine hits of engagement and the immediate satisfaction of short-form video, loses its ability to read books and gets stupider and more reactionary as a result. Frankly, I am not immune to this fear—not only because it is my job to write articles and books but because I think it’s good for people to read books, full stop. And the statistics regarding our collective reading habits are not pretty. In a recent National Literacy Trust survey of seventy-six thousand children, aged eight to eighteen, only one in five said they read something daily in their free time, a historically low mark for the survey. In a National Endowment for the Arts poll conducted in 2022, the number of adults who said they had read at least one book in the past year dipped below fifty per cent, down roughly ten per cent from a decade before. | Một trong những viễn cảnh tận thế thường được nhắc đến khi nói về mạng xã hội đại khái là thế này: một công chúng nghiện Internet, bị móc câu bởi những cú “dopamine” từ tương tác và sự thỏa mãn tức thì của video ngắn, dần đánh mất khả năng đọc sách, rồi trở nên ngu ngơ và phản ứng cực đoan hơn. Thành thật mà nói, tôi không miễn nhiễm với nỗi sợ đó — không chỉ vì công việc của tôi là viết bài và viết sách, mà còn vì tôi tin rằng đọc sách là điều tốt cho con người, chấm hết. Và các con số về thói quen đọc của chúng ta thì chẳng mấy khả quan. Trong một khảo sát gần đây của National Literacy Trust với bảy mươi sáu nghìn trẻ em từ tám đến mười tám tuổi, chỉ một trong năm em cho biết mình đọc thứ gì đó mỗi ngày trong thời gian rảnh — mức thấp nhất trong lịch sử khảo sát này. Còn theo một cuộc thăm dò của National Endowment for the Arts năm 2022, tỷ lệ người trưởng thành nói rằng họ đã đọc ít nhất một cuốn sách trong năm qua đã tụt xuống dưới năm mươi phần trăm, giảm khoảng mười phần trăm so với một thập kỷ trước. |

| Does that mean that people are less literate in general? Counterintuitively, there has never been a time in history when people have spent more time reading words, even if it’s just text messages on their phones. We can agree that most of this reading is less edifying than books are, but I do wonder if the downturn in book reading, and its relationship to our online habits, might be more complicated than we are inclined to conclude. | Vậy điều đó có nghĩa là con người nói chung đang kém hiểu biết chữ nghĩa hơn sao? Nghe có vẻ ngược đời, nhưng chưa bao giờ trong lịch sử con người lại dành nhiều thời gian để đọc chữ như hiện nay — dù phần lớn chỉ là tin nhắn trên điện thoại. Ta có thể đồng ý rằng phần lớn kiểu đọc này ít giá trị bồi đắp hơn so với sách, nhưng tôi vẫn tự hỏi liệu sự sụt giảm trong việc đọc sách, cùng mối quan hệ của nó với thói quen trực tuyến của chúng ta, có phức tạp hơn những gì ta thường vội vàng kết luận hay không. |

| It is, for instance, much easier to find information now—information we might once have looked for in books, say, and also information about the books we might consider reading. Maybe, in the age of the internet, many of us, as informed readers, only want to read one book, tailored very specifically to our interests, every couple of years. | Chẳng hạn, ngày nay việc tìm kiếm thông tin trở nên dễ dàng hơn rất nhiều — những thông tin mà trước đây ta có thể phải tìm trong sách, và cả thông tin về chính những cuốn sách mà ta cân nhắc sẽ đọc. Có lẽ, trong thời đại Internet, nhiều người trong chúng ta, với tư cách là những độc giả có hiểu biết, chỉ muốn đọc một cuốn sách duy nhất, được “đo ni đóng giày” rất sát với mối quan tâm của mình, vài năm một lần. |

| Does that explain a lot of what’s happening? Probably not; more likely, most of us are just stuck in our phones more. Still, I do believe we need to change how we think about literacy, and what it means. | Liệu như vậy có giải thích được phần lớn những gì đang diễn ra không? Có lẽ là không; khả năng cao hơn là hầu hết chúng ta chỉ đơn giản là bị mắc kẹt trong điện thoại nhiều hơn. Dù vậy, tôi tin rằng chúng ta cần thay đổi cách nghĩ về khả năng đọc và ý nghĩa của nó. |

| Imagine a guy; let’s call him Dave. He’s a busy lawyer who lives in the Midwest and has a keen interest in American military history. On Reddit, he finds a community of people who share their favorite titles on the subject. Over time, in this forum, Dave learns which of his fellow-posters are aligned with his own tastes. He becomes choosier about which books he reads—a more efficient reader, in a sense, though one who may read fewer books. Dave also listens to podcasts, watches long YouTube videos, and even participates in live-stream seminars about his favorite moments from the Battle of Antietam, or whatever. | Hãy tưởng tượng một người đàn ông — cứ gọi anh ta là Dave. Dave là một luật sư bận rộn sống ở vùng Trung Tây nước Mỹ, và có niềm đam mê đặc biệt với lịch sử quân sự Hoa Kỳ. Trên Reddit, anh tìm thấy một cộng đồng những người chia sẻ các đầu sách yêu thích về chủ đề này. Theo thời gian, trong diễn đàn ấy, Dave dần nhận ra ai có gu giống mình. Anh trở nên kén chọn hơn trong việc chọn sách — theo một nghĩa nào đó, là một người đọc hiệu quả hơn, dù có thể đọc ít sách hơn. Dave còn nghe podcast, xem những video YouTube dài, thậm chí tham gia các buổi hội thảo trực tuyến về những khoảnh khắc anh yêu thích trong Trận Antietam, hay đại loại thế. |

| Is Dave less informed—less literate?—than he would have been had he read three books that year instead of two? | Vậy Dave có kém hiểu biết hơn — kém “biết đọc” hơn — so với việc anh đọc ba cuốn sách trong năm thay vì hai cuốn hay không? |

| A second, related question: can our online lives actually replicate that craggy, slow feeling of an in-person book club or classroom? Or is there something about the internet’s recommendation architecture and its instant provision of information that turns everything into a speedy optimization run? | Một câu hỏi liên quan khác: liệu đời sống trực tuyến của chúng ta có thể tái tạo được cảm giác gồ ghề, chậm rãi của một câu lạc bộ sách hay lớp học ngoài đời thực không? Hay có điều gì đó trong kiến trúc gợi ý của Internet và cách nó cung cấp thông tin tức thì đã biến mọi thứ thành một cuộc chạy đua tối ưu hóa tốc độ? |

| I started thinking about this question after reading a list by the writer Celine Nguyen titled “Notes on being a writer in the 21st century.” Nguyen, who publishes heady critical essays on Substack, has some appealingly contrarian thoughts. For instance, she points out that “well before AI slop, we had human-generated slop.” And she makes a convincing case that social media and the internet might cause people to read smarter, even if it also causes them to read fewer books: | Tôi bắt đầu nghĩ về câu hỏi này sau khi đọc một danh sách của nhà văn Celine Nguyễn mang tên “Ghi chép về việc làm nhà văn trong thế kỷ 21”. Nguyễn, người đăng tải những bài tiểu luận phê bình nặng ký trên Substack, có nhiều suy nghĩ mang tính phản biện khá hấp dẫn. Chẳng hạn, cô chỉ ra rằng: “từ rất lâu trước khi có rác do AI tạo ra, chúng ta đã có rác do con người tạo ra.” Và cô đưa ra một lập luận thuyết phục rằng mạng xã hội và Internet có thể khiến con người đọc thông minh hơn, ngay cả khi chúng cũng khiến họ đọc ít sách hơn: |

| “A lot of the books that I now think of as foundational to how I see the world, I found out about because people would post on Reddit or Twitter. That is something special about the internet: That you do not need to be in the right social context where these things are automatically accessible to you.” | “Rất nhiều cuốn sách mà giờ đây tôi xem là nền tảng cho cách tôi nhìn nhận thế giới, tôi biết đến chúng vì có người đăng bài trên Reddit hay Twitter. Đó là một điều đặc biệt của Internet: bạn không cần phải ở trong đúng bối cảnh xã hội — nơi những thứ đó vốn dĩ đã sẵn sàng tiếp cận với bạn.” |

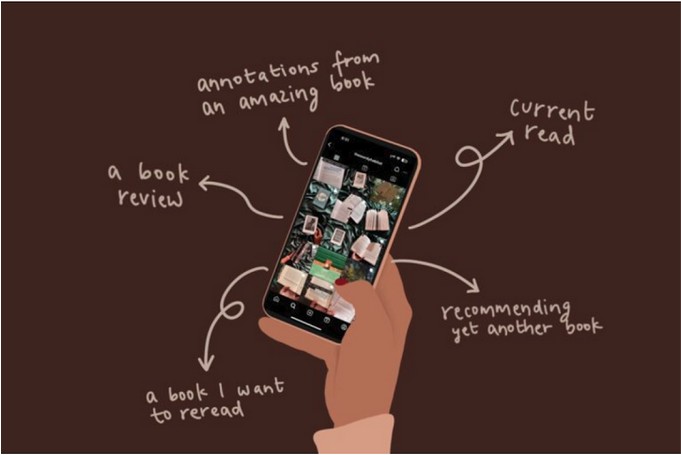

| Nguyen is hardly alone in this experience. BookTok, the sprawling and informal literary community on TikTok, has pushed many people to read outside their usual interests. You don’t have to dig deep into X, Reddit, or Instagram to find reading suggestions that would never appear on the year-end lists in newspapers or magazines, or on the rolls of the major annual awards. Obscure literary titles are reaching people they might not have reached before. | Nguyễn không hề đơn độc trong trải nghiệm này. BookTok — cộng đồng văn chương rộng lớn, lỏng lẻo trên TikTok — đã thúc đẩy nhiều người đọc vượt ra khỏi những mối quan tâm quen thuộc của họ. Bạn không cần đào sâu vào X, Reddit hay Instagram để tìm thấy những gợi ý đọc mà sẽ chẳng bao giờ xuất hiện trong các danh sách tổng kết cuối năm của báo chí hay tạp chí, hoặc trong danh sách đề cử của các giải thưởng lớn thường niên. Những đầu sách văn học ít người biết đến đang tiếp cận được những độc giả mà trước đây có lẽ chúng chưa từng chạm tới. |

| But, if we accept Nguyen’s proposition, and conclude that some of us are slogging through fewer bad books and getting more quickly to the stuff we like, does that actually constitute an improvement in reading culture? | Nhưng nếu ta chấp nhận lập luận của Nguyễn, và kết luận rằng một số người trong chúng ta đang vật lộn với ít sách dở hơn và nhanh chóng đi thẳng đến những thứ mình thích, thì liệu điều đó có thực sự cấu thành một sự cải thiện trong văn hóa đọc hay không? |

| Let’s place our hypothetical friend Dave, the military-history buff, in a book club that requires him to read a whole bunch of books he might have never picked up—the majority of which he finds pointless and a waste of his time. The club also provides a community of in-person friends with whom he can debate and disagree and even argue about what book should be next on the queue. Dave might not read many more books than he would have without the club, and he may enjoy the ones he reads less; the quality of the information he’s receiving may even deteriorate. He might find himself back in the same Reddit threads, hunting down things that are tailored to his interests. | Hãy đặt người bạn giả định Dave của chúng ta — anh chàng mê lịch sử quân sự — vào một câu lạc bộ sách buộc anh phải đọc cả loạt cuốn mà có lẽ anh chưa bao giờ tự nguyện cầm lên, phần lớn trong số đó anh thấy vô bổ và phí thời gian. Câu lạc bộ ấy cũng mang lại cho anh một cộng đồng bạn bè ngoài đời, nơi anh có thể tranh luận, bất đồng, thậm chí cãi vã xem cuốn nào sẽ được đọc tiếp theo. Dave có thể không đọc nhiều sách hơn so với khi không tham gia câu lạc bộ, và thậm chí còn ít thích những cuốn mình đọc; chất lượng thông tin anh tiếp nhận có khi còn đi xuống. Rốt cuộc, anh lại thấy mình quay về những chuỗi thảo luận quen thuộc trên Reddit, tiếp tục săn lùng những thứ được thiết kế riêng cho mối quan tâm của mình. |

| But there are social benefits to reading something together. Someone might be able to jolt him out of his narrow tranche of interests. The experience of reading can benefit from the rockier mental terrain that books provide; the boredom and impatience that longer texts sometimes inspire can help push and prod one’s thinking more than things that are perfectly distilled. | Nhưng việc cùng nhau đọc một thứ gì đó vẫn mang lại những lợi ích xã hội rõ ràng. Có người có thể kéo Dave ra khỏi lát cắt sở thích quá hẹp của anh ta. Trải nghiệm đọc cũng có thể được bồi đắp từ địa hình tinh thần gập ghềnh mà sách mang lại; sự chán nản và nôn nóng mà những văn bản dài đôi khi gây ra có thể thúc đẩy, khuấy động tư duy nhiều hơn so với những thứ đã được chắt lọc đến mức hoàn hảo. |

| I asked Nguyen whether she felt that her vision of a more finely tuned and online reading public might obviate the need for the in-person book club or literary society or writing workshop. She said that although social media and learning about books through the internet likely accelerated exploration, it also could, in her experience, restrict people almost entirely to their own tastes. “You have the ability to create a filter bubble that’s more impermeable,” she said. | Tôi hỏi Nguyễn liệu cô có nghĩ rằng viễn cảnh về một công chúng đọc ngày càng được tinh chỉnh và diễn ra chủ yếu trên mạng có khiến các câu lạc bộ sách trực tiếp, các hội văn chương hay các workshop viết trở nên không còn cần thiết hay không. Cô nói rằng dù mạng xã hội và việc biết đến sách qua Internet có thể đẩy nhanh quá trình khám phá, thì theo kinh nghiệm của cô, chúng cũng có thể gần như giam hãm con người trong chính gu của mình. “Bạn có khả năng tạo ra một bong bóng lọc còn khó xuyên thủng hơn,” cô nói. |

| Social media does create a powerful consensus—on the internet, everything tends to grow quickly toward one source of light— and an argument can be made that a slower, more fractured network of in-person, localized arguments might ultimately offer up more intellectual variety. When I asked Nguyen about this, she mentioned the Ninth Street Women, a group of Abstract Expressionist artists who worked in the postwar period, and her own displaced nostalgia for the idea of artists and writers meeting in physical spaces with similar goals in mind. “It just inherently feels more vibrant if it’s in a physical space than if you Substack notes at the same time that all your friends are posting on Substack notes,” she said. But she also pointed out that such movements tend to be quite insidery, and that a lot of the most successful writers on platforms like Substack are people who might not exactly fit into the New York City literati. | Mạng xã hội quả thực tạo ra một sự đồng thuận rất mạnh — trên Internet, mọi thứ dường như đều nhanh chóng hướng về cùng một nguồn sáng — và người ta hoàn toàn có thể lập luận rằng một mạng lưới tranh luận trực tiếp, chậm rãi và phân mảnh hơn, mang tính địa phương hơn, rốt cuộc lại có thể đem đến sự đa dạng trí tuệ lớn hơn. Khi tôi hỏi Nguyễn về điều này, cô nhắc đến Ninth Street Women, một nhóm nghệ sĩ theo trường phái Biểu hiện Trừu tượng hoạt động trong giai đoạn hậu chiến, và nỗi hoài niệm xa xứ của chính cô về ý tưởng các nghệ sĩ và nhà văn gặp gỡ nhau trong những không gian vật lý, cùng hướng đến những mục tiêu tương tự. “Về bản chất, nó sống động hơn khi diễn ra trong một không gian thật, so với việc bạn đăng ghi chú trên Substack trong lúc tất cả bạn bè của bạn cũng đang đăng ghi chú trên Substack,” cô nói. Tuy vậy, cô cũng chỉ ra rằng những phong trào như thế thường khá khép kín, và rằng nhiều cây bút thành công nhất trên các nền tảng như Substack lại là những người không hẳn thuộc giới văn chương New York. |

| This seems undeniably true to me. It might be nice to go to the same bars and contribute to the same small journals and stare very seriously at the same art work in the same galleries, but such a life feels both anachronistic and annoying today. | Điều này, với tôi, là không thể phủ nhận. Có lẽ sẽ rất thú vị nếu được đến cùng những quán bar, cộng tác cho cùng những tạp chí nhỏ, và đứng ngắm cùng những tác phẩm nghệ thuật trong cùng những phòng trưng bày với vẻ mặt nghiêm túc y hệt nhau, nhưng kiểu đời sống ấy ngày nay vừa mang tính hoài cổ lạc thời, vừa có phần phiền toái. |

| In another of her notes for writers, Nguyen proclaims: | Trong một ghi chép khác dành cho người viết, Nguyễn tuyên bố: |

| “I, controversially, am pro-social media. If you are writing about art, you just make all your social media about contemporary art and art critics and new art releases, and you create this funneled world that reinforces the thing you’re trying to do.” | “Một cách gây tranh cãi, tôi ủng hộ mạng xã hội. Nếu bạn viết về nghệ thuật, bạn chỉ cần biến toàn bộ mạng xã hội của mình thành nghệ thuật đương đại, các nhà phê bình nghệ thuật và những tác phẩm mới ra mắt, rồi bạn tạo ra một thế giới được dẫn dòng, củng cố chính điều bạn đang cố làm.” |

| I have tried similar tactics in the past, especially when I was writing about specific subjects, such as education policy or A.I. But what I found wasn’t really a sharpening of insight, but, rather, a tightened focus on the social-media consensus, which was largely dictated by the people who posted the most on any given topic. Even in moments when I wasn’t writing directly about some tweet I had seen, I was still gesturing toward it. Writing, in this form, felt more like sticking a comment bubble on an aggregated stream of news stories, social-media posts, and an assortment of video podcasts. Most pundits—at least those who comment on the world in columns, newsletters, or on podcasts—are doing some form of this. Taken together, such writing forms “the discourse.” | Tôi đã từng thử những chiến thuật tương tự, đặc biệt khi viết về các chủ đề cụ thể như chính sách giáo dục hay A.I. Nhưng điều tôi nhận được không hẳn là sự sắc bén hơn trong nhận thức, mà là một tiêu điểm bị siết chặt vào sự đồng thuận trên mạng xã hội — vốn phần lớn bị chi phối bởi những người đăng bài nhiều nhất về một chủ đề nhất định. Ngay cả trong những lúc tôi không trực tiếp viết về một dòng tweet nào đó, tôi vẫn đang ngầm ám chỉ đến nó. Kiểu viết này giống như việc dán một bong bóng bình luận lên một dòng chảy tổng hợp của tin tức, bài đăng mạng xã hội và đủ loại podcast video. Phần lớn các nhà bình luận — ít nhất là những người bình luận về thế giới qua các cột báo, bản tin hay podcast — đều đang làm điều gì đó tương tự. Gộp lại, những hình thức viết này tạo thành cái gọi là “diễn ngôn”. |

| Aggregation, for what it’s worth, is also what large language models can most capably replicate. ChatGPT can’t report new facts or provide much atmospheric detail, but it can inhale everything that’s been written on a specific subject, organize the material, and present it in an orderly fashion. Nguyen’s advice may be correct, but, if it is—and given the popularity of newsletters and political commentary and the decline of the novel and even the big doorstop biography—the future of human writing would seem to be headed directly into the jaws of the A.I. machine. | Và nói cho công bằng, tổng hợp cũng chính là thứ mà các mô hình ngôn ngữ lớn có thể bắt chước giỏi nhất. ChatGPT không thể đưa tin những sự kiện mới hay cung cấp nhiều chi tiết mang tính không khí, nhưng nó có thể “hít” vào mọi thứ đã được viết về một chủ đề cụ thể, sắp xếp lại chất liệu và trình bày chúng một cách gọn gàng. Lời khuyên của Nguyễn có thể là đúng, nhưng nếu đúng như vậy — và xét đến sự phổ biến của newsletter, bình luận chính trị, cùng với sự suy giảm của tiểu thuyết và thậm chí cả những cuốn tiểu sử đồ sộ — thì tương lai của việc viết lách của con người dường như đang lao thẳng vào hàm răng của cỗ máy A.I. |

| How do we respond? Do we seek out formal and stylistic breaks that feel authentically human? Or does everything start to look like slop? And can our attempts to find non-sloppified prose outpace the stylistic variations that the L.L.M.s might be able to generate on their own? | Vậy chúng ta nên phản ứng thế nào? Có phải ta cần chủ động tìm kiếm những đứt gãy về hình thức và phong cách — những thứ mang cảm giác con người một cách chân thực? Hay rồi mọi thứ rốt cuộc cũng sẽ trông như một mớ rác na ná nhau? Và liệu những nỗ lực của chúng ta nhằm tìm ra thứ văn xuôi chưa bị “bình rác hóa” có thể đi nhanh hơn những biến thể phong cách mà các mô hình ngôn ngữ lớn tự tạo ra hay không? |

| Some of the most innovative formal experiments I’ve seen recently have appeared on Substack—including, whatever else you may think of it, Ryan Lizza’s recent serialized, scandalous tell-all about his ex-fiancée, Olivia Nuzzi. Not all writing on social media or in nontraditional forms has turned into slop. But there is value in resisting pure optimization, aggregation, and specialization. Not only for the sake of the humanity of the written word but also because it can be quite lonely at the bottom of a rabbit hole. ■ | Một số thử nghiệm hình thức táo bạo và sáng tạo nhất mà tôi thấy gần đây lại xuất hiện trên Substack — trong đó có, dù bạn nghĩ gì về nó đi nữa, loạt bài nhiều kỳ, đầy tai tiếng và mang tính phơi bày đời tư gần đây của Ryan Lizza về vị hôn thê cũ của anh, Olivia Nuzzi. Không phải mọi thứ được viết trên mạng xã hội hay dưới những hình thức phi truyền thống đều đã biến thành “rác”. Nhưng việc chống lại sự tối ưu hóa thuần túy, sự tổng hợp máy móc và tính chuyên môn hóa quá mức vẫn có giá trị. Không chỉ vì tính người của chữ viết, mà còn bởi vì ở tận đáy của một cái hang thỏ, cảm giác cô đơn có thể rất thật. ■ |

| By Jay Caspian Kang (https://www.newyorker.com/contributors/jay-caspian-kang) | Viết bởi Jay Caspian Kang (https://www.newyorker.com/contributors/jay-caspian-kang) |

| Jay Caspian Kang, a staff writer at The New Yorker, is an Emmy-nominated documentary-film director and the author of “The Loneliest Americans.” Prior to joining The New Yorker, he was an opinion writer for the New York Times. His work has appeared in The New York Review of Books, “This American Life,” and the New York Times Magazine. He lives in Northern California with his family. He was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 2024 for his New Yorker work. | Jay Caspian Kang là cây bút thường trực của tạp chí The New Yorker, đồng thời là đạo diễn phim tài liệu từng được đề cử giải Emmy và là tác giả cuốn sách The Loneliest Americans (Những người Mỹ cô đơn nhất). Trước khi gia nhập The New Yorker, anh từng là cây bút chuyên mục ý kiến của tờ New York Times. Các tác phẩm của anh cũng từng xuất hiện trên The New York Review of Books, chương trình This American Life, và New York Times Magazine. Anh hiện sống cùng gia đình ở miền Bắc California. Năm 2024, anh là một trong những ứng viên chung kết cho Giải Pulitzer hạng mục bình luận nhờ loạt bài viết trên The New Yorker. |

| December 9, 2025 | Ngày 9 tháng 12, năm 2025 |

https://www.newyorker.com/news/fault-lines/if-you-quit-social-media-will-you-read-more-books

| Tập Đọc (literally means “Reading Together”) is a bilingual English-Vietnamese magazine featuring new word annotations, translations, spoken word versions (audio articles), and a free vocabulary list for the community. The project has been maintained since 2020 and has published over 100 issues to date. | Tập Đọc là một tạp chí song ngữ Tiếng Anh – Tiếng Việt, với chú thích từ mới, cung cấp bản dịch, phiên bản bài đọc nói (báo tiếng), và danh sách từ mới miễn phí cho cộng đồng. Dự án được duy trì từ năm 2020 đến nay, hiện đã ra trên 100 số. |

| Readers should be advised that the articles published in Tập Đọc do not necessarily reflect the views, attitudes, and perspectives of the editors. Readers are encouraged to form their own opinions and evaluations through a dialogue between themselves and the authors during their reading process. Only reading writers with whom one agrees is akin to only engaging in conversations with those who compliment you: it’s comfortable, but dangerous. | Các bài viết được đăng trên Tập Đọc không nhất thiết phản ánh quan điểm, thái độ và góc nhìn của người biên tập. Người đọc nên hình thành quan điểm và đánh giá của riêng mình trong cuộc đối thoại giữa bản thân người đọc và tác giả, trong quá trình đọc bài của riêng mình. Việc chỉ đọc những người viết mà ta đồng ý cũng giống như chỉ chịu nói chuyện với những ai khen mình vậy: dễ chịu, nhưng nguy hiểm. |

| If you wish to support any of my projects, I would be profoundly grateful. Any support, no matter how small, will be significantly meaningful in helping me stay motivated or continue these non-profit efforts. | Nếu bạn muốn ủng hộ bất cứ dự án nào của mình, mình xin rất biết ơn. Mọi sự ủng hộ, dù nhỏ, đều sẽ rất có ý nghĩa trong việc giúp mình có động lực, hoặc có khả năng tiếp tục các công việc phi lợi nhuận này. |

| Please send your support to account number: 0491 0000 768 69. Account holder: Nguyễn Tiến Đạt, Vietcombank, Thăng Long branch. | Mọi ủng hộ xin gửi về số tài khoản: 0491 0000 768 69. Chủ tài khoản: Nguyễn Tiến Đạt, ngân hàng Vietcombank, chi nhánh Thăng Long. |

| Da Nang, Tuesday, December 23, 2025 Dat Nguyen | Đà Nẵng, thứ Ba, ngày 23.12.2025 Nguyễn Tiến Đạt (sutucon) |

Bạn có thể tải miễn phí bộ học liệu được xây dựng từ bài đọc này tại đây:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1OkKY7kpwz4y2DxHYqdJ_mpbRCNxhAuu9?usp=sharing

BẢNG CHÚ THÍCH TỪ MỚI

| Từ | Nghĩa tiếng Anh | Nghĩa tiếng Việt | Câu ví dụ |

|---|---|---|---|

| rank jealousy | strong, unpleasant jealousy toward others’ success or happiness | sự ghen tị gay gắt | Social media often makes people feel rank jealousy about other people’s achievements. |

| a scratch golfer | a very skilled golfer who plays without needing extra points | một người chơi golf rất giỏi | The author jokes that quitting his phone would not magically turn him into a scratch golfer. |

| thousand-piece puzzles | large, time-consuming jigsaw puzzles | tranh ghép hình hàng nghìn mảnh | He imagines becoming a parent who does thousand-piece puzzles with his children. |

| ambitious films | films that aim to be serious, meaningful, or culturally important | những bộ phim có tham vọng nghệ thuật | He wonders if he would direct ambitious films after quitting social media. |

| capture the Zeitgeist | to represent the spirit or mood of a particular time | bắt được tinh thần thời đại | The author questions whether he would create films that capture the Zeitgeist. |

| unrest | a feeling of anxiety or dissatisfaction in society | sự bất ổn, lo lắng | Unrest about smartphone addiction has been growing for years. |

| abate | to become weaker or less intense | giảm bớt, lắng xuống | The concern over social media does not seem to abate. |

| panic | a sudden strong feeling of fear or anxiety | sự hoảng loạn | The writer admits he has felt the panic around phone addiction himself. |

| loom (verb) | to appear likely to happen soon, often negatively | cận kề, sắp xảy ra | With a book deadline looming, he decided to quit social media. |

| time-wasting | not useful; causing loss of time | lãng phí thời gian | He wanted to spend less time on time-wasting apps. |

| word-processing app | software used for writing text | ứng dụng soạn thảo văn bản | He hoped more of his screen time would go to his word-processing app. |

| a draft (of a book) | an early, unfinished version of a text | bản thảo | He managed to finish a draft of his book on time. |

| detox (noun) | a period of stopping something unhealthy | giai đoạn “cai”, giải độc | The social-media detox did not change his reading habits as expected. |

| materialize | to actually happen or appear | thực sự xảy ra | The hoped-for benefits never fully materialized. |

| noticeable | easy to see or observe | dễ nhận thấy | The changes were not noticeable in daily life. |

| enviable | causing admiration or jealousy | đáng ngưỡng mộ | He believes reading good books leads to enviable prose. |

| prose | written language in ordinary form | văn xuôi | Reading strong prose pushes him to improve his own writing. |

| prompt (somebody to do something) | to cause someone to do something | thúc đẩy, khiến ai đó làm gì | Good writing can prompt him to start typing quickly. |

| out of a sense of inspiration | motivated by creative excitement | vì cảm hứng | He does not write out of a sense of inspiration, but pressure. |

| out of fear | motivated by worry or anxiety | vì sợ hãi | He writes out of fear of falling behind other writers. |

| chief | most important | chủ yếu, chính | The chief effect of quitting social media was feeling uninformed. |

| doomsday scenario | a prediction of serious negative outcomes | kịch bản tận thế | Some fear a doomsday scenario where people stop reading books. |

| (be) hooked on (something) | to be addicted to something | nghiện | Many people are hooked on social media engagement. |

| dopamine hits | short bursts of pleasure or excitement | cảm giác “phê” tức thời | Social media provides constant dopamine hits. |

| engagement | interaction such as likes, comments, or shares | sự tương tác | Platforms are designed to maximize engagement. |

| short-form video | very short online videos | video ngắn | Short-form video offers fast satisfaction but little depth. |

| reactionary | responding emotionally rather than thoughtfully | phản ứng bốc đồng | Critics fear people become more reactionary online. |

| immune (to something) | not affected by something | miễn nhiễm với | The author says he is not immune to these fears. |

| collective | shared by a group | tập thể | Data shows changes in our collective reading habits. |

| survey | a study that collects information from people | khảo sát | A national survey shows fewer children read daily. |

| dip | a small but noticeable decrease | sự sụt giảm | The number of adults reading books has dipped in recent years. |

| literate | able to read and understand written language | biết đọc, có khả năng đọc hiểu | Fewer books do not necessarily mean people are less literate. |

| counterintuitively | in a way that goes against common expectations | ngược với trực giác | Counterintuitively, people now read more words than ever before. |

| edifying | providing moral or intellectual improvement | mang tính giáo dục, bổ ích | Online reading is often less edifying than reading books. |

| downturn | a general decline or reduction | sự suy giảm | The downturn in book reading worries many people. |

| (be) inclined to | likely to think or behave in a certain way | có xu hướng | We are inclined to blame phones for declining reading habits. |

| conclude | to decide or believe something after thinking | kết luận | Many people quickly conclude that social media harms literacy. |

| informed | having a lot of knowledge about something | có hiểu biết | The author asks whether fewer books mean people are less informed. |

| (be) tailored to | made to suit specific needs or interests | được điều chỉnh cho phù hợp | Online content can be tailored to very specific interests. |

| a keen interest (in something) | a strong interest | niềm quan tâm sâu sắc | Dave has a keen interest in military history. |

| (be) aligned (with something) | to match or agree with something | phù hợp, đồng điệu | He trusts readers whose tastes are aligned with his own. |

| choosy | careful when making choices | kén chọn | Dave becomes more choosy about the books he reads. |

| podcast | an online audio program | podcast | Dave listens to podcasts about military history. |

| live-stream seminar | an educational event broadcast online in real time | hội thảo trực tuyến phát trực tiếp | He even joins live-stream seminars on historical topics. |

| replicate | to copy or reproduce something | tái tạo, mô phỏng | The article asks if online spaces can replicate book clubs. |

| craggy | rough, uneven, and challenging | gồ ghề, khó nhằn | Books offer a craggy reading experience. |

| in-person | happening face to face | trực tiếp | An in-person discussion feels different from an online one. |

| book club | a group that reads and discusses books together | câu lạc bộ đọc sách | A traditional book club forces readers out of their comfort zones. |

| provision | the act of supplying something | sự cung cấp | The internet’s instant provision of information changes reading habits. |

| optimization run | a process focused on maximum efficiency | quá trình tối ưu hóa | Online learning can feel like a constant optimization run. |

| appealingly | in an attractive or pleasing way | một cách hấp dẫn | Nguyen offers appealingly contrarian ideas. |

| contrarian | opposing common opinions | đi ngược số đông | Her contrarian views challenge fears about social media. |

| slop | low-quality, careless content | nội dung rác, kém chất lượng | The internet is often accused of producing cultural slop. |

| AI slop | poor-quality content created by ai | nội dung rác do ai tạo ra | Nguyen notes concerns about AI slop. |

| human-generated slop | low-quality content created by people | nội dung rác do con người tạo | She reminds readers that human-generated slop existed first. |

| foundational | forming the basic structure of something | nền tảng | Some books were foundational to how she sees the world. |

| (be) accessible (to somebody) | easy for someone to reach or obtain | dễ tiếp cận | The internet makes ideas accessible to more people. |

| sprawling | large and spreading in many directions | rộng lớn, lan rộng | BookTok is a sprawling online com |

| obscure | not well known or widely read | ít được biết đến | Social media helps obscure books reach new readers. |

| literary title | the name of a book or written work | tác phẩm văn học | Many literary titles gain attention online rather than in newspapers. |

| proposition | an idea or argument put forward | luận điểm, đề xuất | The author questions Nguyen’s proposition about online reading. |

| slog through (something) | to read or do something slowly and with effort | cố gắng lê bước qua, đọc một cách nặng nhọc | Readers may slog through books they do not enjoy. |

| constitute (something) | to be considered as something | được coi là, cấu thành | Does reading fewer books constitute a decline in literacy? |

| hypothetical | imagined for discussion | giả định | Dave is a hypothetical example used to explain the idea. |

| buff | a person who is very interested in a subject | người rất mê một lĩnh vực | Dave is a military-history buff. |

| pointless | having no value or purpose | vô ích | He finds many book-club choices pointless. |

| a waste of (somebody’s) time | not worth the effort | lãng phí thời gian | Some books feel like a waste of his time. |

| in-person friends | friends met face to face, not online | bạn bè ngoài đời thực | Book clubs offer in-person friends and discussion. |

| debate | to discuss different opinions | tranh luận | Members debate which books should be read next. |

| next on the queue | the next item in line | tiếp theo trong danh sách | They argue about what book should be next on the queue. |

| deteriorate | to become worse in quality | trở nên tệ hơn | The quality of information may deteriorate. |

| social benefits | advantages for relationships and community | lợi ích xã hội | Reading together has clear social benefits. |

| jolt somebody out of something | to suddenly force someone to change | kéo ai đó ra khỏi trạng thái nào đó | A discussion can jolt readers out of narrow thinking. |

| narrow tranche | a very limited range of interests | phạm vi hẹp | Online spaces can trap users in a narrow tranche of topics. |

| rocky | difficult and uneven | gập ghềnh, không dễ dàng | Books offer a rocky reading experience. |

| mental terrain | the landscape of thinking and ideas | “địa hình” tư duy | Long books create a challenging mental terrain. |

| boredom | the feeling of being uninterested | sự chán nản | Boredom can sometimes improve thinking. |

| impatience | difficulty waiting calmly | sự thiếu kiên nhẫn | Reading long texts may cause impatience. |

| push and prod one’s thinking | to challenge and stimulate thought | thúc đẩy tư duy | Books push and prod one’s thinking more deeply. |

| perfectly distilled | reduced to its simplest form | được cô đọng hoàn hảo | Online content is often perfectly distilled. |

| finely tuned | carefully adjusted and optimized | được tinh chỉnh kỹ | Online readers may become more finely tuned. |

| obviate the need for (something) | to make something unnecessary | khiến điều gì đó không còn cần thiết | Online communities may obviate the need for book clubs. |

| in-person book club | a physical reading group | câu lạc bộ đọc sách trực tiếp | She doubts the in-person book club will disappear. |

| literary society | a group focused on literature | hội nhóm văn học | Literary discussion once centered on literary societies. |

| writing workshop | a group for practicing and discussing writing | hội thảo / nhóm học viết | Writers used to gather in writing workshops. |

| accelerate | to make something happen faster | đẩy nhanh | The internet can accelerate discovery of books. |

| restrict | to limit | hạn chế | Algorithms may restrict readers to their tastes. |

| a filter bubble | an online environment showing only similar ideas | “bong bóng lọc” thông tin | Social media can create a strong filter bubble. |

| impermeable | not allowing ideas to pass through | khó xuyên thủng, khép kín | Filter bubbles can become almost impermeable. |

| consensus | a shared general opinion | sự đồng thuận | Social media often creates a strong consensus. |

| fractured | broken into smaller, separate parts | bị chia nhỏ, phân mảnh | Offline networks are slower and more fractured. |

| localized | limited to a specific place | mang tính địa phương | Localized communities may encourage varied ideas. |

| ultimately | in the end | cuối cùng | Ultimately, offline spaces may offer more diversity. |

| intellectual variety | a range of different ideas and viewpoints | sự đa dạng trí tuệ | In-person debate can increase intellectual variety. |

| postwar period | the time after a war | thời kỳ hậu chiến | The group worked during the postwar period. |

| displaced | feeling out of place or disconnected | lệch chỗ, xa rời | She expresses a displaced sense of longing. |

| nostalgia (for something) | a sentimental longing for the past | nỗi hoài niệm | She feels nostalgia for older artistic communities. |

| inherently | naturally and essentially | vốn dĩ, tự thân | Physical spaces feel more inherently lively. |

| vibrant | full of life and energy | sôi động, sống động | In-person meetings feel more vibrant. |

| insidery | reflecting the views of a small inner group | mang tính “người trong cuộc” | Old literary circles felt insidery. |

| literati | well-known literary intellectuals | giới trí thức văn chương | Substack writers are not all part of the literati. |

| undeniably true | clearly and certainly true | không thể phủ nhận | This observation feels undeniably true. |

| journals | serious magazines or academic publications | tạp chí học thuật | Writers once published in small journals. |

| anachronistic | belonging to the past, not modern times | lỗi thời | That lifestyle now feels anachronistic. |

| proclaim | to declare publicly | tuyên bố | Nguyen openly proclaims her support for social media. |

| controversially | in a way that causes disagreement | gây tranh cãi | She controversially says she is pro-social media. |

| pro-(something) | in favor of something | ủng hộ điều gì đó | She describes herself as pro-social media. |

| contemporary art | modern art from the present time | nghệ thuật đương đại | She focuses her feeds on contemporary art. |

| new art releases | recently published or shown artworks | các tác phẩm nghệ thuật mới ra mắt | She follows new art releases online. |

| funneled world | a tightly focused information environment | thế giới thông tin bị “dồn kênh” | Social media can create a funneled world. |

| reinforce | to strengthen or support | củng cố | Algorithms reinforce existing interests. |

| a sharpening of insight | deeper understanding | sự sắc bén hơn trong nhận thức | He did not experience a sharpening of insight. |

| a tightened focus | a narrower concentration | sự tập trung bị thu hẹp | Instead, he felt a tightened focus on consensus. |

| dictate | to control or decide | chi phối | Frequent posters dictate online discussions. |

| gesture toward something | to indirectly refer to something | gợi nhắc, ám chỉ | His writing kept gesturing toward social media debates. |

| a comment bubble | a small reaction added to ongoing content | bong bóng bình luận | Writing felt like adding a comment bubble. |

| aggregated | collected from many sources | được tổng hợp | News feeds are highly aggregated. |

| assortment | a varied collection | một tập hợp đa dạng | The stream included an assortment of media. |

| pundit | a person who gives opinions publicly, especially on politics or culture | nhà bình luận, chuyên gia bình luận | Many pundits comment on the same online topics. |

| column (in newspaper or magazine) | a regular opinion article | chuyên mục, bài bình luận | He compares online writing to a traditional newspaper column. |

| discourse | ongoing discussion or debate | diễn ngôn, cuộc thảo luận chung | Together, these writings form “the discourse.” |

| capably | in a competent or effective way | một cách thành thạo | AI can capably organize existing ideas. |

| replicate | to copy or reproduce | sao chép, tái tạo | AI can replicate common writing patterns. |

| atmospheric detail | sensory details that create mood | chi tiết tạo không khí | AI struggles to provide rich atmospheric detail. |

| big doorstop biography | a very long, heavy biography | tiểu sử dày cộp | Readers are turning away from the big doorstop biography. |

| authentically | in a genuinely human way | một cách chân thực | Writers seek styles that feel authentically human. |

| sloppified | turned into low-quality, careless writing | bị “rác hóa”, kém chất lượng | There is fear that all writing becomes sloppified. |

| non-sloppified | not low-quality or careless | không bị “rác hóa” | Writers hope to produce non-sloppified prose. |

| outpace | to move faster than | vượt qua, đi nhanh hơn | Human creativity must outpace AI imitation. |

| scandalous | causing shock or public outrage | gây tai tiếng | He mentions a scandalous serialized story. |

| tell-all | a work revealing private details | tác phẩm phơi bày mọi chuyện | The piece is described as a tell-all. |

| ex-fiancée | a former person someone was engaged to | vị hôn thê cũ | The story is about the writer’s ex-fiancée. |

Leave a comment