In 1886, the Russian novelist Lev Tolstoy published a short story called “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” Its protagonist, a poor farmer named Pahóm, dreams of becoming a landowner. He thinks, “If I had plenty of land, I shouldn’t fear the Devil himself!” The Devil is listening, and decides to orchestrate a series of events. The story ends as Pahóm collapses on a fatal quest to gain more land, a stream of blood flowing from his mouth.

Tolstoy wasn’t an economist; in fact, he was so profligate with money that he once lost his family’s rural estate in a card game. But “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” contains many insights about money and psychology.

Illustration by Simon Bailly

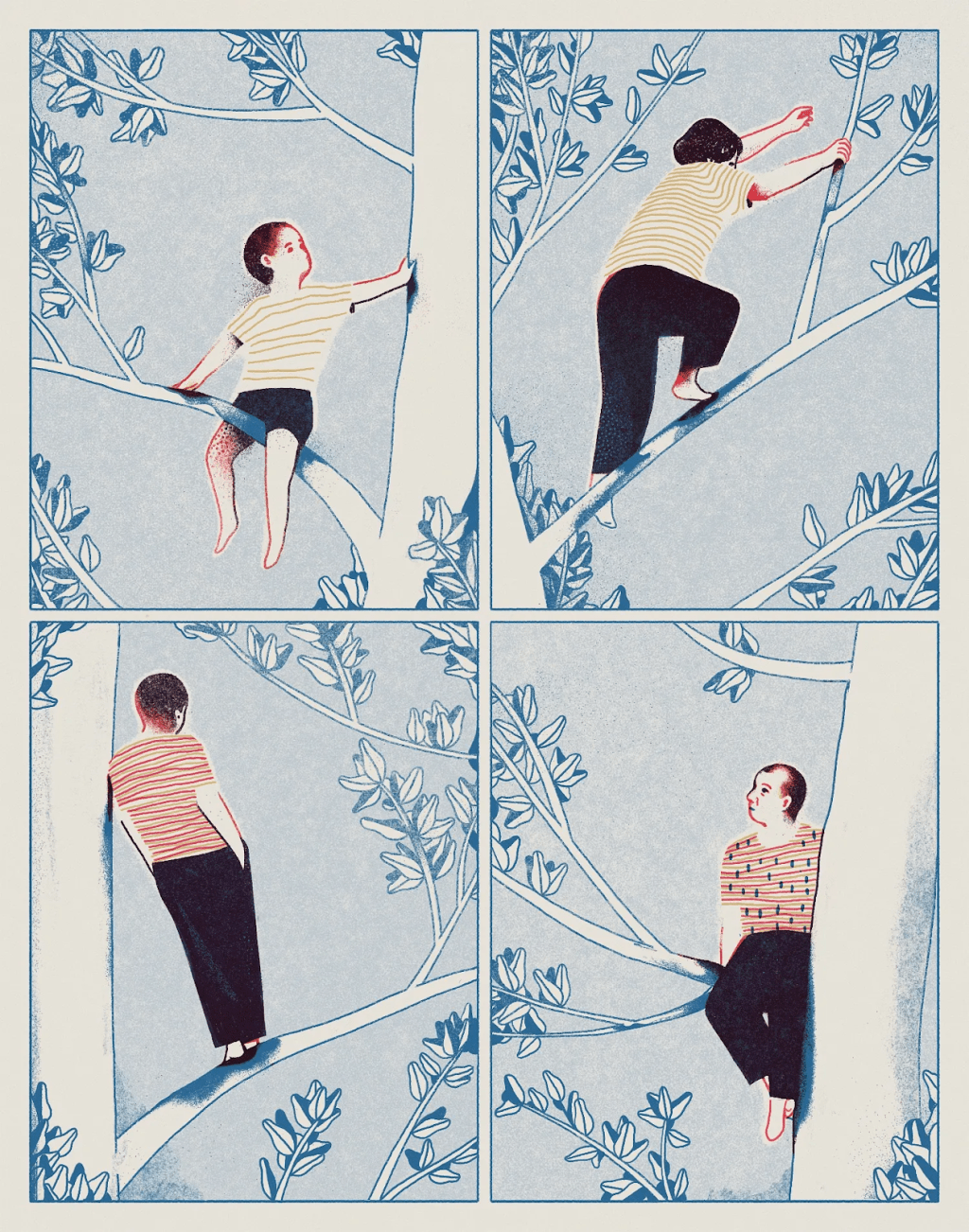

In 1886, Lev Tolstoy published a short story called “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” Its protagonist, a poor farmer named Pahóm, dreams of becoming a landowner. He thinks, “If I had plenty of land, I shouldn’t fear the Devil himself!” The Devil is listening, and decides to orchestrate a series of events. Pahóm borrows money to buy more land. He raises cattle and grows corn and becomes prosperous. He sells his lands at a profit and moves to a new area where he can buy vast tracts for low prices. He’s briefly content, but as he grows accustomed to his new prosperity he becomes dissatisfied. He still has to rent land to grow wheat, and he quarrels with poorer people about the same land. Owning even more would make everything easier.

Pahóm soon hears of the Baskhírs, a distant community of people who live on a fertile plain by a river and will sell land for almost nothing. He buys tea and wine and other gifts and travels to meet them. Their chief explains that they sell land by the day. For the minuscule price of a thousand rubles, Pahóm can have as much land as he can cover in a day of walking, as long as he returns to the starting point before sunset. The next morning, Pahóm sets out through the high grass of the steppe. The farther he goes, the better the land seems. He walks faster and faster, farther and farther, tempted by distant prospects. Then the sun starts to slip toward the horizon. He turns back, but fatigue sets in. His feet grow bruised, his heart hammers, and his shirt and trousers become soaked with sweat. With aching legs, he charges up the hill toward the chief, who exclaims, “He has gained much land!” But Pahóm has already collapsed, and a stream of blood flows from his mouth. The Baskhírs click their tongues in pity, and then Pahóm’s servant takes the spade and digs a simple grave, six feet long. The question in the story’s title is answered: that’s all the land a man needs.

Tolstoy wasn’t an economist; in fact, he was so profligate with money that he once lost his family’s rural estate in a card game. But “How Much Land Does a Man Need?” contains many insights about money, psychology, and economic thinking. Pahóm, pursuing growth at all costs, seeks only to maximize his profit; he expands relentlessly into new regions of perceived opportunity, ignoring negative “externalities,” such as the exhausted soil and the damage he does to his relationships. For a time, his cycle of expansion looks like success, and at every stage Pahóm has apparently good reasons for expanding. His neighbors are obnoxious; not renting is more efficient; good land is cheap. In a narrow sense, he’s behaving rationally.

But a series of seemingly rational decisions somehow culminates in catastrophe. At each new level of wealth, instead of enjoying the resources he already has, Pahóm quickly becomes dissatisfied, returning to a previous level of happiness. Late in the story, when he is desperately exhausted, he could easily choose to forfeit his thousand rubles, rest in the grass, and then walk leisurely back to the starting place. Yet he believes that he’s invested so much effort that it would be foolish to stop, and continues pouring more energy into a doomed endeavor. Moments before his death, Pahóm realizes his essential error. “I have grasped too much and ruined the whole affair,” he thinks. How could a calculated business venture have gone so horribly wrong?

One way to understand Pahóm’s misfortune would be to say that he failed to think clearly. Today, behavioral economists, who study the psychology of economic life, talk about the “hedonic treadmill” and the “sunk-cost fallacy,” considering them errors in reasoning; they’d probably say that Pahóm falls victim to these patterns of faulty thinking. But Tolstoy saw the same patterns differently, as risks within a landscape of moral possibilities. The Devil himself uses them to gain power over Pahóm’s soul; the acquisitive quest they inspire has moral consequences, deforming Pahóm’s beliefs and behavior. Prior to the Devil’s interference, Pahóm had humble values: “Though a peasant’s life is not a fat one, it is a long one,” his wife says at the beginning of the story. “We shall never grow rich, but we shall always have enough to eat.” A life unencumbered by self-destructive greed was available to him. Yet, as Tolstoy’s story winds to a close, the Baskhírs’ sharply limited interest in wealth strikes Pahóm not as a challenge to his own values but as a business opportunity; he perceives them not as wise but as “ignorant.”

Tolstoy saw a moral dimension to economic thinking. There was a time when mainstream economists saw it, too. “It seems clearer every day that the moral problem of our age is concerned with the Love of Money,” the economist John Maynard Keynes wrote, in 1925. Keynes, like Tolstoy, recognized that many major topics of economics are inescapably moral and political: the “master-economist,” he wrote on another occasion, “must be mathematician, historian, statesman, philosopher—in some degree.” With an optimism that proved premature, Keynes described a future when “the love of money as a possession—as distinguished from the love of money as a means to the enjoyments and realities of life—will be recognized for what it is, a somewhat disgusting morbidity.” Critiquing the “decadent” and “individualistic” nature of international capitalism after the First World War, he wrote, “it is not intelligent, it is not beautiful, it is not just, it is not virtuous.”

Today, it’s hard to imagine many mainstream economists deploying this kind of moral and aesthetic language. Instead, economics relies on a technocratic, quasi-scientific vocabulary, which obscures the ethical and political questions that lie at the heart of the discipline. In a 1953 essay, for instance, Milton Friedman argued that economics could be “an ‘objective’ science, in precisely the same sense as any of the physical sciences.” Countless other economists have subsequently accepted this view. From this perspective, the moral evaluations of Keynes, Tolstoy, or anyone else are irrelevant. This pose of scientific impartiality allows mainstream economists to smuggle all sorts of dubious claims—that economic growth requires high inequality, that increasing corporate concentration is inevitable, or that people can only be motivated to work by desperation—into policy and discourse. This becomes an excuse for maintaining the status quo, which is presented as the result of inevitable and immutable “laws.” In the famous phrase of Margaret Thatcher, “There is no alternative.”

And yet, some economists, reviving the attitudes of Keynes and Tolstoy, have appeared more open to the idea that economics is a branch of political philosophy. Thomas Piketty has described “the powerful illusion of eternal stability, to which the uncritical use of mathematics in the social sciences sometimes leads.” The economist Albert Hirschman suggested that those at the top of society often seek to “impress the general public” by proclaiming that their status is the “inevitable outcome of current processes.” He went on, “But after so many failed prophecies, is it not in the interest of social science to embrace complexity, be it at some sacrifice of its claim to predictive power?” In 1900, in a book titled “The Slavery of Our Times,” Tolstoy struck some of the same notes. “At the end of the eighteenth century, the people of Europe began little by little to understand that what had seemed a natural and inevitable form of economic life, namely, the position of peasants who were completely in the power of their lords, was wrong, unjust, and immoral, and demanded alteration,” he wrote. You can’t change the laws of physics. You can, however, change the rules of the economic game.

But how should we change them? It’s possible to imagine a future in which people look back on economic systems that fail to reflect the true price of goods—including their impact on workers, the natural world, and future generations—as uncontroversially wrong. They may see current corporate ownership models that permit extraordinary concentrations of power and wealth, for instance, as absurd. But what will replace them? What are the real alternatives? Tolstoy’s approach isn’t likely to strike us as appealing. He concentrates, for the most part, on moral and spiritual reforms.

And yet it’s possible to marry economics and morality, by adopting economic models and policies that give tangible reality to the otherwise empty platitude that a better world is possible. Initiatives such as participatory budgeting, climate budgeting, job guarantees, employee ownership, true prices, genuine living wages, a public utility-style job market for irregular labor, less dogmatic economics education, and new investment-capital models that decrease wealth inequality are all powerful elements of a more just and sustainable economy. Better yet, they already exist. There’s no stronger response to charges of utopianism than showing models that are already working.

It’s possible to incorporate these approaches into our existing world. Mayors and elected officials, for example, can implement climate or participatory budgeting without making drastic changes elsewhere in government. Leaders of workforce boards and officials in the Department of Labor can help create public markets for irregular workers—after all, private-sector gig-work systems, like Uber, already exist. Business owners can convert to novel-ownership structures (as Patagonia did, in 2022), or start selling goods using true prices. Investors can use their capital in ways that reduce wealth inequality. Professors of economics and business can make students and the public aware of alternative approaches. And ordinary people who don’t hold powerful positions can support these efforts. The town of Mondragón, in northern Spain, is home to the world’s largest integrated network of worker and multi-stakeholder coöperatives, and has also experimented with participatory budgeting. The city of Amsterdam, in which true pricing originated, also practices a version of climate budgeting. And many businesses with shared ownership also pay a genuine living wage. Real people are living a vision of the economy as a place of moral action and accountability, rather than a value-free, self-regulating zone of unalterable laws.

In 1933, just before the opening of the World Economic Conference, Keynes addressed a radio audience. “The world’s needs are desperate,” he said. “We have, all of us, mismanaged our affairs. We live miserably in a world of the greatest potential wealth.” Of economists, he asked, “Isn’t the present shocking state of the world partly due to the lack of imagination which they have shown?” Tolstoy wasn’t an economist, but he can teach us a valuable economic lesson. We must shift our notion of the economy from an impersonal sphere of abstract forces into a human arena of ethical decisions. To do otherwise is, to paraphrase, Keynes, not intelligent, beautiful, just, or virtuous.

By Nick Romeo

More from him: https://www.newyorker.com/contributors/nick-romeo

Original article: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/annals-of-inquiry/an-economics-lesson-from-tolstoy

January 16, 2024

This is drawn from “The Alternative: How to Build a Just Economy.”

https://www.amazon.com/Alternative-How-Build-Just-Economy/dp/1541701593

Bạn có thể tải miễn phí bộ học liệu được xây dựng từ bài đọc này tại đây:

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1zGg1zcErbHN_nghs06MT6dYcnYSpAsYo?usp=sharing

Tập Đọc (literally means “Reading Together”) is a bilingual English-Vietnamese journal featuring new word annotations, translations, spoken word versions (audio articles), and a free vocabulary list for the community. The project has been maintained since 2020 and has published over 80 issues to date.

Readers should be advised that the articles published in Tập Đọc do not necessarily reflect the views, attitudes, and perspectives of the editors. Readers are encouraged to form their own opinions and evaluations through a dialogue between themselves and the authors during their reading process. Only reading writers with whom one agrees is akin to only engaging in conversations with those who compliment you: it’s comfortable, but dangerous.

Hope this helps.

If you wish to support any of my projects, I would be profoundly grateful. Any support, no matter how small, will be significantly meaningful in helping me stay motivated or continue these non-profit efforts.

Please send your support to account number: 0491 0000 768 69. Account holder: Nguyễn Tiến Đạt, Vietcombank, Thăng Long branch.

Đà Nẵng, February 16, 2024

Nguyễn Tiến Đạt (sutucon)

BẢNG CHÚ THÍCH TỪ MỚI

| STT | Từ mới | Phiên âm | Nghĩa tiếng Anh | Nghĩa tiếng Việt |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | protagonist | /prəʊˈtæɡənɪst/ | the main character in a story, play, novel, or other narrative who plays a central role, especially in facing challenges or undergoing adventures. | nhân vật chính |

| 2 | landowner | /ˈlændˌəʊnə/ | a person who owns land, especially large amounts of land. | chủ đất |

| 3 | the Devil | /ðə/ /ˈdɛvᵊl/ | a supernatural being often represented in Christianity as the supreme spirit of evil and adversary of God; used metaphorically here to represent temptation or evil intentions. | quỷ dữ |

| 4 | orchestrate | /ˈɔːkɪstreɪt/ | to arrange or direct the elements of a situation to produce a desired effect, often in a skillful or cunning way. | dàn xếp, tổ chức |

| 5 | prosperous | /ˈprɒspərəs/ | successful in material terms; flourishing financially. | thịnh vượng |

| 6 | at a profit | /æt/ /ə/ /ˈprɒfɪt/ | earning more money than the amount spent; making money from a transaction or investment. | có lãi |

| 7 | tracts | /trækts/ | large areas of land. | mảnh đất lớn |

| 8 | content | /ˈkɒntɛnt/ | in a state of peaceful happiness; satisfied. | hài lòng |

| 9 | grows accustomed to | /ɡrəʊz/ /əˈkʌstəmd/ /tuː/ | becomes familiar with something over time, adjusting to it. | quen với |

| 10 | prosperity | /prɒsˈpɛrəti/ | the state of being prosperous; wealth or success. | sự thịnh vượng |

| 11 | dissatisfied | /ˌdɪsˈsætɪsfaɪd/ | not content or happy with the current situation; feeling that one’s desires or needs are not being met. | không hài lòng |

| 12 | quarrels with | /ˈkwɒrᵊlz/ /wɪð/ | to argue or have a dispute with someone. | cãi vã với |

| 13 | fertile | /ˈfɜːtaɪl/ | capable of producing abundant vegetation or crops; rich in nutrients. | màu mỡ |

| 14 | plain | /pleɪn/ | a large area of flat land with few trees. | đồng bằng |

| 15 | chief | /ʧiːf/ | the leader or head of a group or community. | thủ lĩnh |

| 16 | minuscule | /ˈmɪnəskjuːl/ | extremely small; tiny. | rất nhỏ |

| 17 | cover | /ˈkʌvə/ | to traverse or travel across a certain area. | đi qua |

| 18 | sets out | /sɛts/ /aʊt/ | begins a journey or task with a particular goal in mind. | bắt đầu |

| 19 | steppe | /stɛp/ | a large area of flat, unforested grassland. | thảo nguyên |

| 20 | tempted by | /ˈtɛmptɪd/ /baɪ/ | attracted to or enticed by something, especially that which is not necessarily beneficial. | bị cám dỗ bởi |

| 21 | prospects | /ˈprɒspɛkts/ | the possibility or likelihood of some future event occurring; here, it refers to opportunities or potential lands to acquire. | triển vọng |

| 22 | the horizon | /ðə/ /həˈraɪzᵊn/ | the line at which the earth’s surface and the sky appear to meet. | chân trời |

| 23 | fatigue | /fəˈtiːɡ/ | extreme tiredness resulting from mental or physical exertion or illness. | mệt mỏi |

| 24 | bruised | /bruːzd/ | injured, typically with discoloration but without breaking the skin. | bầm tím |

| 25 | hammers | /ˈhæməz/ | beats rapidly and forcefully; here, it refers to the heart beating quickly due to exertion. | đập mạnh |

| 26 | soaked | /səʊkt/ | extremely wet; saturated with liquid. | ướt sũng |

| 27 | aching | /ˈeɪkɪŋ/ | experiencing pain or soreness. | đau nhức |

| 28 | charges up | /ˈʧɑːʤɪz/ /ʌp/ | moves quickly and with determination, often towards a goal or target. | lao lên |

| 29 | exclaims | /ɪksˈkleɪmz/ | to speak suddenly and with strong feeling. | thốt lên |

| 30 | collapse | /kəˈlæps/ | to fall down or give way due to physical weakness. | sụp đổ |

| 31 | pity | /ˈpɪti/ | the feeling of sorrow and compassion caused by the suffering and misfortunes of others. | thương hại |

| 32 | economist | /iˈkɒnəmɪst/ | a person who studies or has expertise in the field of economics, which is the study of how societies, governments, businesses, households, and individuals allocate their scarce resources. | nhà kinh tế học |

| 33 | profligate | /ˈprɒflɪɡɪt/ | recklessly extravagant or wasteful in the use of resources. | hoang phí |

| 34 | rural estate | /ˈrʊərəl/ /ɪˈsteɪt/ | a large area of land in the countryside, often with a large house, owned by a person, family, or organization. | bất động sản nông thôn |

| 35 | insights | /ˈɪnsaɪts/ | deep, intuitive understandings or perceptions of the true nature of something. | cái nhìn sâu sắc |

| 36 | psychology | /saɪˈkɒləʤi/ | the scientific study of the mind and behavior, including the study of consciousness, perception, emotions, and much more. | tâm lý học |

| 37 | economic thinking | /ˌiːkəˈnɒmɪk/ /ˈθɪŋkɪŋ/ | the process of considering and analyzing issues and decisions in terms of costs, benefits, incentives, and consequences within the framework of economics. | tư duy kinh tế |

| 38 | at all costs | /æt/ /ɔːl/ /kɒsts/ | regardless of the effort, expense, or sacrifice necessary. | bằng mọi giá |

| 39 | relentlessly | /rɪˈlɛntləsli/ | in a manner that is unceasingly intense, harsh, or inflexible. | không ngừng nghỉ |

| 40 | perceived | /pəˈsiːvd/ | regarded in a particular way; seen or understood from a certain perspective. | được nhận thức |

| 41 | externalities | /ˌɛkstɜːˈnælətiz/ | costs or benefits that affect a party who did not choose to incur those costs or benefits, often referring to the unintended consequences of economic activities on third parties. | các tác động bên ngoài |

| 42 | exhausted | /ɪɡˈzɔːstɪd/ | extremely tired; depleted of energy or resources. | kiệt sức |

| 43 | obnoxious | /əbˈnɒkʃəs/ | extremely unpleasant, especially in a way that is offensive or annoying. | khó chịu |

| 44 | rationally | /ˈræʃᵊnᵊli/ | in a manner that is based on or in accordance with reason or logic. | một cách hợp lý |

| 45 | culminate | /ˈkʌlmɪneɪt/ | reach a climax or point of highest development. | đạt đến đỉnh điểm |

| 46 | catastrophe | /kəˈtæstrəfi/ | a sudden and widespread disaster or a momentous tragic event ranging from extreme misfortune to utter overthrow or ruin. | thảm họa |

| 47 | forfeit | /ˈfɔːfɪt/ | lose or be deprived of (property or a right or privilegeas a penalty for wrongdoing. | mất quyền lợi |

| 48 | leisurely | /ˈlɛʒəli/ | acting or done at leisure; unhurried or relaxed. | thong thả |

| 49 | a doomed endeavor | /ə/ /duːmd/ /ɪnˈdɛvə/ | an effort or attempt that is certain to fail or lead to a disastrous outcome. | một nỗ lực bất thành |

| 50 | grasp | /ɡrɑːsp/ | seize and hold firmly; understand fully. | nắm bắt |

| 51 | the whole affair | /ðə/ /həʊl/ /əˈfeə/ | the entire situation, matter, or event being referred to. | toàn bộ sự việc |

| 52 | calculated | /ˈkælkjəleɪtɪd/ | (of an actiondone with full awareness of the likely consequences; carefully planned or intended. | tính toán |

| 53 | business venture | /ˈbɪznɪs/ /ˈvɛnʧə/ | a business undertaking involving risk in the expectation of gain. | dự án kinh doanh |

| 54 | misfortune | /ˌmɪsˈfɔːʧuːn/ | bad luck; an unfortunate condition or event. | rủi ro |

| 55 | behavioral economists | /bɪˈheɪvjərəl/ /iˈkɒnəmɪsts/ | economists who study the effects of psychological, cognitive, emotional, cultural, and social factors on the economic decisions of individuals and institutions and how those decisions vary from those implied by classical theory. | nhà kinh tế học hành vi |

| 56 | hedonic treadmill | /hiːˈdɒn.ɪk/ /ˈtrɛdmɪl/ | a theory suggesting that people repeatedly return to their baseline level of happiness, regardless of what happens to them. | bánh xe hedonic |

| 57 | sunk-cost fallacy | /sʌŋk/-/kɒst/ /ˈfæləsi/ | the misconception that further investments (of money, time, resourcesjustify continued investment in a decision, based on the cumulative prior investment, despite new evidence suggesting that the cost, beginning immediately, of continuing the decision outweighs the expected benefit. | sai lầm về chi phí chìm |

| 58 | reasoning | /ˈriːzᵊnɪŋ/ | the action of thinking about something in a logical, sensible way. | lý luận |

| 59 | pattern | /ˈpætᵊn/ | a repeated decorative design or a regular and intelligible form or sequence discernible in the way in which something happens or is done. | mẫu vẽ |

| 60 | landscape | /ˈlænskeɪp/ | all the visible features of an area of land, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal. | phong cảnh |

| 61 | moral | /ˈmɒrᵊl/ | concerned with the principles of right and wrong behavior and the goodness or badness of human character. | đạo đức |

| 62 | acquisitive | /əˈkwɪzɪtɪv/ | excessively interested in acquiring money or material things. | ham muốn có được |

| 63 | quest | /kwɛst/ | a long or arduous search for something. | cuộc tìm kiếm |

| 64 | consequences | /ˈkɒnsɪkwənsɪz/ | a result or effect of an action or condition. | hậu quả |

| 65 | deform | /dɪˈfɔːm/ | distort the shape or form of; make misshapen. | làm biến dạng |

| 66 | interference | /ˌɪntəˈfɪərᵊns/ | the action of interfering or the process of being interfered with. | sự can thiệp |

| 67 | humble | /ˈhʌmbᵊl/ | having or showing a modest or low estimate of one’s importance. | khiêm tốn |

| 68 | values | /ˈvæljuːz/ | a person’s principles or standards of behavior; one’s judgment of what is important in life. | giá trị |

| 69 | peasant | /ˈpɛzᵊnt/ | a poor smallholder or agricultural laborer of low social status (historically, working land owned by others. | nông dân |

| 70 | unencumbered by | /ˌʌnɪnˈkʌmbəd/ /baɪ/ | not having any burden or impediment. | không bị cản trở bởi |

| 71 | self-destructive | /sɛlf/-/dɪˈstrʌktɪv/ | behaving in a way that is likely to cause harm or damage to oneself. | tự hủy hoại |

| 72 | greed | /ɡriːd/ | intense and selfish desire for something, especially wealth, power, or food. | tham lam |

| 73 | winds to a close | /wɪndz/ /tuː/ /ə/ /kləʊz/ | comes to an end; concludes. | kết thúc |

| 74 | limited | /ˈlɪmɪtɪd/ | restricted in size, amount, or extent; few, small, or short. | hạn chế |

| 75 | a challenge to | /ə/ /ˈʧælɪnʤ/ /tuː/ | an invitation to engage in a contest or competition, often implying a test of one’s abilities or resources in a demanding but stimulating undertaking. | thách thức với |

| 76 | perceive | /pəˈsiːv/ | become aware or conscious of (something; come to realize or understand. | nhận thức |

| 77 | dimension | /dɪˈmɛnʃᵊn/ | an aspect or feature of a situation, problem, or thing. | kích thước |

| 78 | mainstream | /ˈmeɪnstriːm/ | accepted by or common among the majority of people; typical or conventional. | chủ đạo |

| 79 | inescapably | /ˌɪnɪˈskeɪpəbᵊli/ | unable to be avoided or denied; inevitably. | không thể tránh khỏi |

| 80 | statesman | /ˈsteɪtsmən/ | a skilled, experienced, and respected political leader or figure. | nhà chính trị |

| 81 | optimism | /ˈɒptɪmɪzᵊm/ | hopefulness and confidence about the future or the successful outcome of something. | lạc quan |

| 82 | premature | /ˈprɛməʧə/ | occurring or done before the usual or proper time; too early. | sớm, chưa đến lúc |

| 83 | possession | /pəˈzɛʃᵊn/ | something that is owned or possessed by someone. | sở hữu |

| 84 | distinguish | /dɪsˈtɪŋɡwɪʃ/ | to recognize or treat (someone or something) as different. | phân biệt |

| 85 | means | /miːnz/ | an action or system by which a result is brought about; a method. | phương tiện, cách thức |

| 86 | somewhat | /ˈsʌmwɒt/ | to a moderate extent or by a moderate amount; rather. | phần nào, đến một mức độ nào đó |

| 87 | disgusting | /dɪsˈɡʌstɪŋ/ | arousing revulsion or strong indignation; very unpleasant. | ghê tởm |

| 88 | morbidity | /mɔːˈbɪdəti/ | the condition of being diseased or unhealthy; an interest in unpleasant subjects, especially death and disease. | sự morbid, ám ảnh về cái chết hoặc bệnh tật |

| 89 | critiquing | /krɪˈtiːkɪŋ/ | examining and judging carefully; evaluating. | phê bình |

| 90 | decadent | /ˈdɛkədᵊnt/ | characterized by or reflecting a state of moral or cultural decline. | suỵ đổ, thoái hóa |

| 91 | individualistic | /ˌɪndɪˌvɪʤuəˈlɪstɪk/ | characterized by independent and self-reliant habits or values; emphasizing the importance of individuality and personal autonomy. | cá nhân chủ nghĩa |

| 92 | just | /ʤʌst/ | based on or behaving according to what is morally right and fair. | công bằng |

| 93 | virtuous | /ˈvɜːʧuəs/ | having or showing high moral standards. | đức hạnh |

| 94 | deploy | /dɪˈplɔɪ/ | to use something or someone, especially in an effective way. | triển khai, sử dụng |

| 95 | aesthetic | /iːsˈθɛtɪk/ | concerned with beauty or the appreciation of beauty. | thẩm mỹ |

| 96 | technocratic | /ˌteknəˈkrætɪk/ | relating to or characterized by the government or control of society or industry by technical experts. | kỹ trị |

| 97 | quasi-scientific | /ˈkweɪzaɪ/-/ˌsaɪənˈtɪfɪk/ | seemingly scientific but not truly based on scientific principles. | có vẻ khoa học |

| 98 | obscures | /əbˈskjʊəz/ | makes unclear or difficult to understand. | làm mờ, che khuất |

| 99 | ethical | /ˈɛθɪkᵊl/ | relating to moral principles or the branch of knowledge dealing with these. | đạo đức |

| 100 | lie at the heart of | /laɪ/ /æt/ /ðə/ /hɑːt/ /ɒv/ | to be a very important or essential part of something. | nằm ở trung tâm của |

| 101 | discipline | /ˈdɪsəplɪn/ | a branch of knowledge, typically one studied in higher education. | lĩnh vực, ngành học |

| 102 | physical sciences | /ˈfɪzɪkᵊl/ /ˈsaɪənsɪz/ | the branches of science such as physics, chemistry, and geology that deal with non-living materials. | khoa học tự nhiên |

| 103 | irrelevant | /ɪˈrɛləvᵊnt/ | not connected with or relevant to something. | không liên quan |

| 104 | impartiality | /ɪmˌpɑːʃiˈæləti/ | equal treatment of all rivals or disputants; fairness. | sự công bằng, không thiên vị |

| 105 | smuggle | /ˈsmʌɡᵊl/ | to move (goods) illegally into or out of a country, or to introduce ideas subtly and secretly. | lén lút đưa vào |

| 106 | dubious | /ˈdjuːbiəs/ | hesitating or doubting; not to be relied upon; suspect. | đáng ngờ |

| 107 | inequality | /ˌɪnɪˈkwɒləti/ | the state of not being equal, especially in status, rights, and opportunities. | bất bình đẳng |

| 108 | corporate concentration | /ˈkɔːpᵊrət/ /ˌkɒnsənˈtreɪʃᵊn/ | the process by which a market is dominated by a few large companies. | sự tập trung doanh nghiệp |

| 109 | inevitable | /ɪˈnɛvɪtəbᵊl/ | certain to happen; unavoidable. | không thể tránh khỏi |

| 110 | immutable | /ɪˈmjuːtəbᵊl/ | unchanging over time or unable to be changed. | bất biến |

| 111 | desperation | /ˌdɛspəˈreɪʃᵊn/ | a state of despair, typically one that results in rash or extreme behavior. | sự tuyệt vọng |

| 112 | discourse | /ˈdɪskɔːs/ | written or spoken communication or debate. | luận thảo, tranh luận |

| 113 | the status quo | /ðə/ /ˈsteɪtəs/ /kwəʊ/ | the existing state of affairs, especially regarding social or political issues. | trạng thái hiện tại |

| 114 | reviving | /rɪˈvaɪvɪŋ/ | bringing back into use or consciousness; reawakening interest in something that was previously ignored or forgotten. | hồi sinh |

| 115 | political philosophy | /pəˈlɪtɪkᵊl/ /fɪˈlɒsəfi/ | a branch of philosophy that involves discussions about government, political policies, the rights and obligations of citizens, justice, liberty, and the enforcement of a legal code by authority. | triết học chính trị |

| 116 | proclaim | /prəˈkleɪm/ | to announce officially or publicly; to declare something one believes in, especially in a public context. | tuyên bố |

| 117 | embrace | /ɪmˈbreɪs/ | to accept or support willingly and enthusiastically. | đón nhận |

| 118 | predictive | /prɪˈdɪktɪv/ | relating to the ability to predict or foretell future events based on certain data or observations. | có tính dự báo |

| 119 | unjust | /ʌnˈʤʌst/ | not based on or behaving according to what is morally right and fair. | bất công |

| 120 | immoral | /ɪˈmɒrᵊl/ | not conforming to accepted standards of morality; not ethical or virtuous. | vô đạo đức |

| 121 | alteration | /ˌɒltəˈreɪʃᵊn/ | the act or process of changing something, making it different in some way. | sự thay đổi |

| 122 | uncontroversially | /ˌʌnˌkɒntrəˈvɜːʃᵊli/ | in a manner that does not cause dispute or disagreement because of a general agreement. | một cách không gây tranh cãi |

| 123 | permit | /ˈpɜːmɪt/ | to allow; to give authorization or consent for something to happen. | cho phép |

| 124 | absurd | /əbˈsɜːd/ | wildly unreasonable, illogical, or inappropriate; ridiculous. | vô lý |

| 125 | appealing | /əˈpiːlɪŋ/ | attractive or interesting; able to draw favorable attention or interest. | hấp dẫn |

| 126 | spiritual | /ˈspɪrɪʧuəl/ | relating to or affecting the human spirit or soul as opposed to material or physical things. | tâm linh |

| 127 | reforms | /ˌriːˈfɔːmz/ | changes or improvements to a system, organization, or practice, especially to make it more effective or fair. | cải cách |

| 128 | marry | /ˈmæri/ | to combine or blend two things together effectively. | kết hợp |

| 129 | adopt | /əˈdɒpt/ | to take up or start to use or follow (an idea, method, or course of action). | áp dụng |

| 130 | tangible | /ˈtænʤəbᵊl/ | perceptible by touch or clear and definite; real. | hữu hình |

| 131 | empty platitude | /ˈɛmpti/ /ˈplætɪtjuːd/ | a statement that is often presented as significant but is actually trivial and lacking in meaning. | lời nói sáo rỗng |

| 132 | initiatives | /ɪˈnɪʃətɪvz/ | projects or strategies introduced to solve a problem or make improvements. | sáng kiến |

| 133 | participatory budgeting | /pɑːˌtɪsɪˈpeɪtᵊri/ /ˈbʌʤɪtɪŋ/ | a democratic process in which community members decide how to allocate part of a public budget. | ngân sách tham gia |

| 134 | public utility | /ˈpʌblɪk/ /juːˈtɪləti/ | a company providing essential services to the public such as water, electricity, or transportation, often regulated by the government. | tiện ích công cộng |

| 135 | irregular labor | /ɪˈrɛɡjələ/ /ˈleɪbə/ | work that does not follow standard or regular hours; it may be temporary, freelance, or part-time. | lao động không ổn định |

| 136 | dogmatic | /dɒɡˈmætɪk/ | inclined to lay down principles as incontrovertibly true, without consideration of evidence or the opinions of others. | một cách máy móc |

| 137 | inequality | /ˌɪnɪˈkwɒləti/ | the state of not being equal, especially in status, rights, and opportunities. | bất bình đẳng |

| 138 | sustainable | /səˈsteɪnəbᵊl/ | capable of being maintained at a certain rate or level; conserving an ecological balance by avoiding depletion of natural resources. | bền vững |

| 139 | utopianism | /juːˈtəʊpiənɪzᵊm/ | the aim of creating a perfect society, often seen as unrealistic or idealistic. | chủ nghĩa lý tưởng |

| 140 | private-sector | /ˈpraɪvət/-/ˈsɛktə/ | the part of the national economy that is not under direct government control. | khu vực tư nhân |

| 141 | gig-work | /ɡɪɡ/-/wɜːk/ | a labor market characterized by the prevalence of short-term contracts or freelance work as opposed to permanent jobs. | công việc tự do |

| 142 | integrated | /ˈɪntɪɡreɪtɪd/ | combined into a whole; unified. | tích hợp |

| 143 | multi-stakeholder | /ˈmʌltɪ/-/ˈsteɪkˌhəʊldə/ | involving multiple parties or groups, each holding a stake or interest in a company or project. | đa bên liên quan |

| 144 | accountability | /əˌkaʊntəˈbɪləti/ | the responsibility of an individual or organization to account for its activities, accept responsibility for them, and disclose the results in a transparent manner. | trách nhiệm giải trình |

| 145 | self-regulating | /sɛlf/-/ˈrɛɡjəleɪtɪŋ/ | capable of controlling oneself or itself without external intervention. | tự điều chỉnh |

| 146 | unalterable | /ʌnˈɔːltərəbᵊl/ | not able to be changed or modified. | không thể thay đổi |

| 147 | address | /əˈdrɛs/ | to speak to a group of people formally. | phát biểu |

| 148 | desperate | /ˈdɛspᵊrət/ | feeling or showing a hopeless sense that a situation is so bad as to be impossible to deal with. | tuyệt vọng |

| 149 | mismanage | /ˌmɪsˈmænɪʤ/ | to manage badly or incompetently. | quản lý kém |

| 150 | shift | /ʃɪft/ | to change the place, position, or direction of something. | chuyển đổi |

| 151 | notion | /ˈnəʊʃᵊn/ | a conception of or belief about something. | khái niệm |

| 152 | impersonal | /ɪmˈpɜːsᵊnᵊl/ | not influenced by, showing, or involving personal feelings. | khách quan |

| 153 | sphere | /sfɪə/ | a field or area of activity, interest, or expertise. | lĩnh vực |

| 154 | abstract | /ˈæbstrækt/ | existing in thought or as an idea but not having a physical or concrete existence. | trừu tượng |

| 155 | arena | /əˈriːnə/ | a place or scene of activity, debate, or conflict. | đấu trường |

| 156 | ethical | /ˈɛθɪkᵊl/ | relating to moral principles or the branch of knowledge dealing with these. | đạo đức |

| 157 | paraphrase | /ˈpærəfreɪz/ | to express the meaning of something written or spoken using different words, especially to achieve greater clarity. | diễn giải lại |

BÀI TẬP ĐIỀN TỪ

| STT | Câu điền từ | Bản dịch tiếng Việt |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | He has a ………………………………………………………… fascination with the darker aspects of human history, which some find unsettling. | Anh ta có niềm đam mê đến mức bệnh hoạn với những khía cạnh đen tối của lịch sử loài người, điều mà một số người cảm thấy đáng lo ngại. |

| 2 | In , Keynes ………………………………………………………… a radio audience about the desperate state of the world economy. | Năm 2014, Keynes phát biểu trước khán giả đài về tình trạng tuyệt vọng của nền kinh tế thế giới. |

| 3 | Some cultural traditions are …………………………………………………………, passed down unchanged through generations. | Một số truyền thống văn hóa là bất biến, được truyền lại không thay đổi qua nhiều thế hệ. |

| 4 | Real people are living a vision of the economy as a place of moral action and …………………………………………………………, rather than a value-free zone of unalterable laws. | Những con người thực sự đang sống trong tầm nhìn về nền kinh tế như một nơi của hành động đạo đức và trách nhiệm giải trình, chứ không phải là một khu vực không có giá trị của những luật lệ không thể thay đổi. |

| 5 | His ………………………………………………………… about the future was infectious, making everyone around him feel hopeful. | Sự lạc quan của anh ấy về tương lai đã lan tỏa, khiến mọi người xung quanh anh ấy cảm thấy hy vọng. |

| 6 | Artists often use a specific ………………………………………………………… in their work to make it recognizable. | Các nghệ sĩ thường sử dụng một mô thức cụ thể trong tác phẩm của họ để khiến nó dễ nhận biết. |

| 7 | Acts of kindness and ………………………………………………………… are highly valued in many cultures. | Những hành động tử tế và đạo đức được đánh giá cao ở nhiều nền văn hóa. |

| 8 | In , in a book titled “The Slavery of Our Times,” Tolstoy struck some of the same notes about the ………………………………………………………… power of economic systems. | Trong cuốn sách có tựa đề “Nô lệ của thời đại chúng ta”, Tolstoy đã đưa ra một số lưu ý tương tự về sức mạnh dự đoán của các hệ thống kinh tế. |

| 9 | Investing in the stock market without research is …………………………………………………………; it’s likely to result in significant losses. | Đầu tư vào thị trường chứng khoán mà không nghiên cứu là một nỗ lực thất bại; nó có thể dẫn đến tổn thất đáng kể. |

| 10 | Owning a ………………………………………………………… is a dream for many who wish to escape the hustle and bustle of city life. | Sở hữu một bất động sản ở nông thôn là giấc mơ của nhiều người mong muốn thoát khỏi sự hối hả và nhộn nhịp của cuộc sống thành phố. |

| 11 | The ………………………………………………………… of Mongolia is known for its vast, open spaces. | Đồng bằng Mông Cổ được biết đến với không gian rộng mở, rộng mở. |

| 12 | ………………………………………………………… Opinions are often considered safe and widely accepted in society. | Những ý kiến chính thống thường được coi là an toàn và được chấp nhận rộng rãi trong xã hội. |

| 13 | The consequences of our actions are …………………………………………………………; we cannot avoid them no matter how hard we try. | Hậu quả của hành động của chúng ta là không thể tránh khỏi; chúng ta không thể tránh chúng cho dù chúng ta có cố gắng thế nào đi chăng nữa. |

| 14 | For his journey across the desert, he planned to ………………………………………………………… a distance of miles. | Đối với cuộc hành trình xuyên sa mạc của mình, ông đã lên kế hoạch đi hết một quãng đường dài hàng dặm. |

| 15 | The arrival of the storm was …………………………………………………………, given the weather forecasts. | Sự xuất hiện của cơn bão là không thể tránh khỏi, dựa trên dự báo thời tiết. |

| 16 | And yet, some economists, ………………………………………………………… the attitudes of Keynes and Tolstoy, have appeared more open to the idea that economics is a branch of philosophy. | Tuy nhiên, một số nhà kinh tế học, làm sống lại quan điểm của Keynes và Tolstoy, đã tỏ ra cởi mở hơn với ý tưởng rằng kinh tế học là một nhánh của triết học. |

| 17 | It’s important to ………………………………………………………… between facts and opinions when researching. | Điều quan trọng là phải phân biệt giữa sự thật và ý kiến khi nghiên cứu. |

| 18 | Every action has its …………………………………………………………, whether they are intended or not. | Mọi hành động đều có hậu quả của nó, dù chúng có chủ ý hay không. |

| 19 | The principle of equality ………………………………………………………… the ………………………………………………………… of democratic societies. | Nguyên tắc bình đẳng nằm ở trung tâm của ngành xã hội dân chủ. |

| 20 | It’s possible to imagine a future in which economic systems that fail to reflect the true price of goods are seen as ………………………………………………………… wrong. | Có thể tưởng tượng một tương lai trong đó các hệ thống kinh tế không phản ánh được giá thực của hàng hóa sẽ bị coi là sai không thể tranh cãi. |

| 21 | Excited about the adventure ahead, the group ………………………………………………………… at dawn. | Vui mừng về cuộc phiêu lưu phía trước, cả nhóm lên đường vào lúc bình minh. |

| 22 | The theory was based on ………………………………………………………… evidence, which made it difficult to prove scientifically. | Lý thuyết này dựa trên bằng chứng gần như khoa học, điều này gây khó khăn cho việc chứng minh một cách khoa học. |

| 23 | His comment was deemed ………………………………………………………… to the discussion, as it did not contribute to the main topic. | Bình luận của anh ấy được coi là không liên quan đến cuộc thảo luận vì nó không đóng góp cho chủ đề chính. |

| 24 | True ………………………………………………………… about oneself often come from moments of quiet reflection and introspection. | Những hiểu biết sâu sắc thực sự về bản thân thường đến từ những khoảnh khắc lặng lẽ suy ngẫm và xem xét nội tâm. |

| 25 | The judge is known for being ………………………………………………………… and fair in all his rulings. | Thẩm phán được biết đến là người công bằng và công bằng trong mọi phán quyết của mình. |

| 26 | The goal of these initiatives is to decrease wealth ………………………………………………………… and promote a more sustainable economy. | Mục tiêu của những sáng kiến này là giảm sự giàu có bất bình đẳng và thúc đẩy một nền kinh tế bền vững hơn. |

| 27 | Being ………………………………………………………… financial debt allowed her to pursue her passion without worry. | Việc không bị cản trở bởi nợ tài chính cho phép cô theo đuổi đam mê của mình mà không phải lo lắng. |

| 28 | The project’s success was …………………………………………………………; it happened much sooner than anyone expected. | Sự thành công của dự án là quá sớm; nó xảy ra sớm hơn nhiều so với mọi người mong đợi. |

| 29 | ………………………………………………………… focus on how people actually make decisions, including the irrational ways we often behave. | Các nhà kinh tế học hành vi tập trung vào cách mọi người thực sự đưa ra quyết định, bao gồm cả những cách hành xử phi lý mà chúng ta thường hành xử. |

| 30 | Despite the …………………………………………………………, she kept a positive attitude and continued to work towards her goals. | Bất chấp bất hạnh, cô ấy vẫn giữ thái độ tích cực và tiếp tục hướng tới mục tiêu của mình. |

| 31 | An ………………………………………………………… studies the economic behaviors and trends to predict future market movements. | Một nhà kinh tế nghiên cứu các hành vi và xu hướng kinh tế để dự đoán diễn biến thị trường trong tương lai. |

| 32 | He sold the apartment …………………………………………………………, earning much more than its original purchase price. | Anh ta đã bán căn hộ có lãi, kiếm được nhiều tiền hơn giá mua ban đầu. |

| 33 | To ………………………………………………………… something is to become aware of it through careful observation or consideration. | Nhận thức điều gì đó là nhận thức được nó thông qua sự quan sát hoặc cân nhắc cẩn thận. |

| 34 | The heist was …………………………………………………………, with every step carefully considered to avoid detection. | Vụ cướp đã được tính toán, với từng bước được cân nhắc cẩn thận để tránh bị phát hiện. |

| 35 | With every beat, his heart ………………………………………………………… like a drum in his chest. | Theo từng nhịp đập, trái tim anh đập như trống trong lồng ngực. |

| 36 | After years of hard work, she finally became a ………………………………………………………… with vast lands. | Sau nhiều năm làm việc chăm chỉ, cuối cùng cô đã trở thành địa chủ với những vùng đất rộng lớn. |

| 37 | The ………………………………………………………… is characterized by large, grassy areas with few trees. | Thảo nguyên có đặc điểm là những vùng cỏ rộng lớn và ít cây cối. |

| 38 | Initiatives such as participatory budgeting and climate budgeting are examples of economic ………………………………………………………… aimed at creating a more equitable society. | Các sáng kiến như lập ngân sách có sự tham gia và lập ngân sách khí hậu là những ví dụ về cải cách kinh tế nhằm tạo ra một xã hội công bằng hơn. |

| 39 | And yet it’s possible to ………………………………………………………… economics and morality by adopting economic models that give tangible reality to the idea that a better world is possible. | Tuy nhiên, có thể kết hợp kinh tế và đạo đức bằng cách áp dụng các mô hình kinh tế mang lại thực tế hữu hình cho ý tưởng rằng một thế giới tốt đẹp hơn là có thể. |

| 40 | A ………………………………………………………… person considers the impact of their actions on others and strives to do what is right. | Một người có đạo đức xem xét tác động của hành động của mình đối với người khác và cố gắng làm điều đúng đắn. |

| 41 | The earthquake was a ………………………………………………………… that left the city in ruins and thousands without homes. | Trận động đất là một thảm họa khiến thành phố trở thành đống đổ nát và hàng nghìn người mất nhà cửa. |

| 42 | He could not ………………………………………………………… the concept no matter how many times it was explained. | Anh ấy không thể nắm bắt được khái niệm này cho dù nó có được giải thích bao nhiêu lần đi chăng nữa. |

| 43 | The ………………………………………………………… in the tech industry raises concerns about market fairness and competition. | Sự tập trung của công ty trong ngành công nghệ làm dấy lên lo ngại về sự công bằng và cạnh tranh của thị trường. |

| 44 | A true ………………………………………………………… is not only a politician but also a visionary leader who cares for the nation’s welfare. | Một chính khách thực thụ không chỉ là một chính trị gia mà còn là một nhà lãnh đạo có tầm nhìn, người quan tâm đến phúc lợi của quốc gia. |

| 45 | Their new ………………………………………………………… aims to revolutionize how we use renewable energy. | Liên doanh kinh doanh mới của họ nhằm mục đích cách mạng hóa cách chúng ta sử dụng năng lượng tái tạo. |

| 46 | Education is a ………………………………………………………… to a better life, offering opportunities for growth and development. | Giáo dục là phương tiện để có một cuộc sống tốt đẹp hơn, mang lại cơ hội tăng trưởng và phát triển. |

| 47 | He went on, “But after so many failed prophecies, is it not in the interest of social science to ………………………………………………………… complexity, be it at some sacrifice of its claim to power?” | Ông tiếp tục, “Nhưng sau rất nhiều lời tiên tri thất bại, chẳng phải khoa học xã hội nên nắm lấy sự phức tạp, hay phải hy sinh quyền lực của nó sao?” |

| 48 | In medieval times, ………………………………………………………… worked the land to earn their living, often under harsh conditions. | Vào thời trung cổ, nông dân làm việc trên đất để kiếm sống, thường trong những điều kiện khắc nghiệt. |

| 49 | The ………………………………………………………… nature of the rumor raised questions about its truth. | Bản chất đáng ngờ của tin đồn đã đặt ra câu hỏi về sự thật của nó. |

| 50 | Pollution is an example of ………………………………………………………… that affects individuals who are not directly involved in its production. | Ô nhiễm là một ví dụ về các tác động bên ngoài ảnh hưởng đến những cá nhân không trực tiếp tham gia vào quá trình sản xuất ô nhiễm. |

| 51 | Many fairy tales warn about making deals with …………………………………………………………. | Nhiều câu chuyện cổ tích cảnh báo về việc giao dịch với Quỷ dữ. |

| 52 | The accident ………………………………………………………… his car, making it unrecognizable. | Vụ tai nạn đã làm biến dạng chiếc xe của anh ấy, khiến nó không thể nhận dạng được. |

| 53 | Thomas Piketty has described economics as a branch of ………………………………………………………… …………………………………………………………. | Thomas Piketty đã mô tả kinh tế học như một nhánh của triết học chính trị. |

| 54 | We must ………………………………………………………… our notion of the economy from an impersonal sphere of abstract forces into a human arena of ethical decisions. | Chúng ta phải chuyển quan niệm của mình về nền kinh tế từ một phạm vi khách quan của các lực lượng trừu tượng sang một phạm vi con người của các quyết định đạo đức. |

| 55 | Decisions should be made ………………………………………………………… to avoid unnecessary risks and consequences. | Các quyết định nên được đưa ra một cách hợp lý để tránh những rủi ro và hậu quả không đáng có. |

| 56 | The ………………………………………………………… valley was ideal for growing a variety of crops. | Thung lũng màu mỡ là nơi lý tưởng để trồng nhiều loại cây trồng. |

| 57 | The town of Mondragón is home to the world’s largest integrated network of worker and ………………………………………………………… coöperatives. | Thị trấn Mondragón là nơi có mạng lưới tích hợp lớn nhất thế giới giữa công nhân và hợp tác xã nhiều bên liên quan. |

| 58 | The economist Albert Hirschman suggested that those at the top of society often seek to impress the general public by ………………………………………………………… that their status is the “inevitable outcome of current processes.” | Nhà kinh tế học Albert Hirschman cho rằng những người ở tầng lớp thượng lưu trong xã hội thường tìm cách gây ấn tượng với công chúng bằng cách tuyên bố rằng địa vị của họ là “kết quả tất yếu của các quá trình hiện tại”. |

| 59 | She was amazed by the ………………………………………………………… detail of the miniature painting. | Cô ấy rất ngạc nhiên trước chi tiết rất nhỏ của bức tranh thu nhỏ. |

| 60 | The ………………………………………………………… for the new technology seemed promising, attracting many investors. | Triển vọng về công nghệ mới có vẻ đầy hứa hẹn, thu hút nhiều nhà đầu tư. |

| 61 | In an ………………………………………………………… society, people prioritize their own goals over the collective good. | Trong một xã hội cá nhân chủ nghĩa, mọi người ưu tiên mục tiêu của riêng mình hơn lợi ích tập thể. |

| 62 | The ………………………………………………………… of an argument can include various perspectives such as emotional, logical, and ethical aspects. | Khía cạnh của một lập luận có thể bao gồm nhiều quan điểm khác nhau như các khía cạnh cảm xúc, logic và đạo đức. |

| 63 | The issue was ………………………………………………………… complicated, more than initially thought. | Vấn đề hơi phức tạp, nhiều hơn suy nghĩ ban đầu. |

| 64 | Political ………………………………………………………… can sometimes hinder the progress of important legislation. | can thiệp chính trị đôi khi có thể cản trở sự tiến bộ của các đạo luật quan trọng. |

| 65 | They may see current corporate ownership models that ………………………………………………………… extraordinary concentrations of power and wealth as absurd. | Họ có thể coi các mô hình sở hữu doanh nghiệp hiện nay cho phép sự tập trung quyền lực và của cải một cách phi thường là điều vô lý. |

| 66 | Falling for the ………………………………………………………… means continuing a project just because you’ve already invested a lot in it, not because it’s the best decision going forward. | Rơi vào ngụy biện chi phí chìm có nghĩa là tiếp tục một dự án chỉ vì bạn đã đầu tư rất nhiều vào nó chứ không phải vì đó là quyết định tốt nhất trong tương lai. |

| 67 | Challenging ………………………………………………………… often requires courage and innovation. | Thách thức hiện trạng thường đòi hỏi lòng dũng cảm và sự đổi mới. |

| 68 | “At the end of the eighteenth century, the people of Europe began little by little to understand that what had seemed a natural and inevitable form of economic life was ………………………………………………………….” | “Vào cuối thế kỷ 18, người dân Châu Âu bắt đầu dần dần hiểu rằng những gì tưởng chừng như là một hình thức tự nhiên và tất yếu của đời sống kinh tế lại bất công.” |

| 69 | They recognized that the position of peasants who were completely in the power of their lords was not only wrong but also ………………………………………………………… and demanded change. | Họ thừa nhận rằng địa vị của những người nông dân hoàn toàn nằm trong quyền lực của lãnh chúa là không những sai trái mà còn vô đạo đức và yêu cầu thay đổi. |

| 70 | Tolstoy’s approach, focusing mostly on moral and ………………………………………………………… reforms, isn’t likely to strike us as appealing today. | Cách tiếp cận của Tolstoy, tập trung chủ yếu vào cải cách đạo đức và tinh thần, dường như không còn hấp dẫn chúng ta ngày nay nữa. |

| 71 | Despite his achievements, he remained …………………………………………………………, always giving credit to his team. | Bất chấp những thành tích của mình, anh ấy vẫn khiêm tốn, luôn ghi công cho đội của mình. |

| 72 | Less ………………………………………………………… economics education could open the door to more diverse and innovative economic thinking. | Giáo dục kinh tế ít giáo điều hơn có thể mở ra cánh cửa cho tư duy kinh tế đa dạng và sáng tạo hơn. |

| 73 | The ………………………………………………………… lifestyle of the early th century led to significant social and moral changes. | Lối sống suy đồi đầu thế kỷ thứ đã dẫn đến những thay đổi đáng kể về xã hội và đạo đức. |

| 74 | They enjoyed a ………………………………………………………… stroll through the park, appreciating every moment of the sunny day. | Họ tận hưởng một cuộc đi dạo nhàn nhã qua công viên, trân trọng từng khoảnh khắc của ngày nắng. |

| 75 | As the sun dipped towards …………………………………………………………, they realized they needed to find shelter quickly. | Khi mặt trời lặn về phía đường chân trời, họ nhận ra rằng mình cần nhanh chóng tìm nơi trú ẩn. |

| 76 | “We have, all of us, ………………………………………………………… our affairs,” Keynes said, highlighting the need for a new approach to economic management. | Keynes nói: “Tất cả chúng ta đều đã quản lý sai công việc của mình, đồng thời nhấn mạnh sự cần thiết phải có một cách tiếp cận mới trong quản lý kinh tế. |

| 77 | The military decided to ………………………………………………………… new strategies to improve defense mechanisms. | Quân đội quyết định triển khai các chiến lược mới để cải thiện cơ chế phòng thủ. |

| 78 | The ………………………………………………………… involved complex negotiations and delicate diplomacy. | Toàn bộ vụ việc liên quan đến các cuộc đàm phán phức tạp và ngoại giao tế nhị. |

| 79 | People usually ………………………………………………………… the climate of the place they live in after a while. | Mọi người thường quen dần với khí hậu nơi họ sống sau một thời gian. |

| 80 | After running the marathon, he was completely ………………………………………………………… and couldn’t take another step. | Sau khi chạy marathon, anh ấy hoàn toàn kiệt sức và không thể bước thêm bước nào nữa. |

| 81 | Engaging in ………………………………………………………… behaviors can be a sign of underlying issues that need to be addressed. | Tham gia vào các hành vi tự hủy hoại có thể là dấu hiệu của những vấn đề cơ bản cần được giải quyết. |

| 82 | The festival …………………………………………………………, signaling the end of summer and the beginning of fall. | Lễ hội kết thúc, báo hiệu sự kết thúc của mùa hè và đầu mùa thu. |

| 83 | After the marathon, she was overwhelmed by ………………………………………………………… and could barely stand. | Sau cuộc chạy marathon, cô ấy bị mệt mỏi choáng ngợp và hầu như không thể đứng vững. |

| 84 | She decided to pursue her dreams …………………………………………………………, no matter the obstacles she might face. | Cô quyết định theo đuổi ước mơ của mình bằng mọi giá, bất chấp những trở ngại mà cô có thể gặp phải. |

| 85 | The ………………………………………………………… suggests that our pursuit of happiness often leads us back to our starting point, no matter what we achieve. | Máy chạy bộ khoái lạc gợi ý rằng việc theo đuổi hạnh phúc thường đưa chúng ta quay trở lại điểm xuất phát, bất kể chúng ta đạt được điều gì. |

| 86 | The ………………………………………………………… smell from the kitchen made it hard to stay in the apartment. | Mùi khó chịu từ nhà bếp khiến việc ở trong căn hộ trở nên khó khăn. |

| 87 | Studying this ………………………………………………………… requires dedication and an analytical mind. | Nghiên cứu ngành học này đòi hỏi sự cống hiến và đầu óc phân tích. |

| 88 | The athlete had to ………………………………………………………… his title after being found guilty of doping. | Vận động viên này đã phải bị tước danh hiệu sau khi bị kết tội sử dụng doping. |

| 89 | The event planner managed to ………………………………………………………… a perfect wedding ceremony despite the challenges. | Người tổ chức sự kiện đã cố gắng sắp xếp một lễ cưới hoàn hảo bất chấp những thách thức. |

| 90 | The national park is one of the largest ………………………………………………………… of untouched wilderness in the region. | Công viên quốc gia là một trong những vùng hoang dã hoang sơ lớn nhất trong khu vực. |

| 91 | His muscles were ………………………………………………………… after the intense workout session. | Cơ bắp của anh ấy đau sau buổi tập luyện cường độ cao. |

| 92 | The committee strives for ………………………………………………………… in evaluating all applications, ensuring no bias. | Ủy ban cố gắng đạt được tính công bằng trong việc đánh giá tất cả các đơn đăng ký, đảm bảo không có sự thiên vị. |

| 93 | After receiving the good news, she felt completely …………………………………………………………. | Sau khi nhận được tin vui, cô cảm thấy hoàn toàn hài lòng. |

| 94 | The research project will ………………………………………………………… in a comprehensive report detailing our findings over the past year. | Dự án nghiên cứu sẽ lên đến đỉnh điểm trong một báo cáo toàn diện trình bày chi tiết những phát hiện của chúng tôi trong năm qua. |

| 95 | The policy changes ………………………………………………………… the true impact on the community, making it hard for citizens to understand. | Những thay đổi chính sách che khuất tác động thực sự đến cộng đồng, khiến người dân khó hiểu. |

| 96 | Making ………………………………………………………… decisions is crucial for leaders to maintain trust and integrity. | Việc đưa ra các quyết định có đạo đức là rất quan trọng đối với các nhà lãnh đạo để duy trì sự tin cậy và liêm chính. |

| 97 | People often find the ………………………………………………………… of waste in food production to be a major ethical issue. | Mọi người thường coi việc lãng phí trong sản xuất thực phẩm là một vấn đề đạo đức nghiêm trọng. |

| 98 | Falling off his bike, his knee was ………………………………………………………… but not seriously injured. | Bị ngã xe đạp, đầu gối của anh ấy bị bầm tím nhưng không bị thương nặng. |

| 99 | Neighbors often ………………………………………………………… over boundary lines that are not clearly defined. | Hàng xóm thường xuyên cãi vã vì ranh giới không được xác định rõ ràng. |

| 100 | The knight embarked on a ………………………………………………………… to find the lost treasure, facing many challenges along the way. | Hiệp sĩ bắt tay vào nhiệm vụ tìm kiếm kho báu bị mất, phải đối mặt với nhiều thử thách trên đường đi. |

| 101 | The startup became ………………………………………………………… within a few years, attracting significant investment. | Công ty khởi nghiệp này trở nên thịnh vượng trong vòng vài năm, thu hút được nguồn đầu tư đáng kể. |

| 102 | Good ………………………………………………………… is essential when solving complex problems. | Lý luận tốt là điều cần thiết khi giải quyết các vấn đề phức tạp. |

| 103 | She viewed her extensive book collection not just as ………………………………………………………… but as gateways to different worlds. | Cô ấy coi bộ sưu tập sách phong phú của mình không chỉ là sở hữu mà còn là cánh cổng dẫn đến các thế giới khác nhau. |

| 104 | Wow! he …………………………………………………………, impressed by the magician’s trick. | Ồ! anh ta kêu lên, bị ấn tượng bởi trò ảo thuật của nhà ảo thuật. |

| 105 | Resources are ………………………………………………………… on this planet, making conservation and sustainable use essential. | Tài nguyên trên hành tinh này là có hạn nên việc bảo tồn và sử dụng bền vững là điều cần thiết. |

| 106 | The detective worked ………………………………………………………… to solve the mystery, leaving no stone unturned. | Vị thám tử đã làm việc không ngừng nghỉ để giải đáp bí ẩn, không bỏ sót một manh mối nào. |

| 107 | The main character in a novel is often referred to as the …………………………………………………………. | Nhân vật chính trong tiểu thuyết thường được gọi là nhân vật chính. |

| 108 | Despite his wealth, he remained ………………………………………………………… with his life, always wanting more. | Bất chấp sự giàu có của mình, anh ấy vẫn không hài lòng với cuộc sống của mình và luôn muốn nhiều hơn nữa. |

| 109 | The field of ………………………………………………………… explores how individuals think, feel, and behave in different situations. | Lĩnh vực tâm lý học khám phá cách các cá nhân suy nghĩ, cảm nhận và hành xử trong các tình huống khác nhau. |

| 110 | The movie was ………………………………………………………… as a masterpiece by critics, despite its initial mixed reception. | Bộ phim được các nhà phê bình coi là kiệt tác, mặc dù ban đầu nó được đón nhận trái chiều. |

| 111 | ………………………………………………………… is crucial when making decisions to ensure they are beneficial in the long term. | Tư duy kinh tế rất quan trọng khi đưa ra các quyết định nhằm đảm bảo chúng có lợi về lâu dài. |

| 112 | In today’s consumer society, being ………………………………………………………… is often seen as a virtue, but it can lead to negative consequences. | Trong xã hội tiêu dùng ngày nay, việc có lợi thường được coi là một đức tính tốt nhưng nó có thể dẫn đến những hậu quả tiêu cực. |

| 113 | Caught in the rain, they were ………………………………………………………… to the skin by the time they reached home. | Bị mắc mưa, họ đã ướt đến tận da khi về đến nhà. |

| 114 | A healthy public ………………………………………………………… is essential for a functioning democracy. | Một diễn ngôn công cộng lành mạnh là điều cần thiết cho một nền dân chủ hoạt động. |

| 115 | Climbing Mount Everest is ………………………………………………………… many mountaineers, testing their skill, endurance, and willpower. | Leo lên đỉnh Everest là một thử thách đối với nhiều người leo núi, kiểm tra kỹ năng, sức bền và ý chí của họ. |

| 116 | He was ………………………………………………………… by the thought of discovering hidden treasures. | Anh ấy bị cám dỗ bởi ý nghĩ khám phá những kho báu ẩn giấu. |

| 117 | Smugglers often ………………………………………………………… illegal goods into the country, bypassing customs. | Những kẻ buôn lậu thường buôn lậu hàng lậu vào nước này, qua mặt hải quan. |

| 118 | The museum’s ………………………………………………………… appeal made it a popular destination for art lovers. | Sức hấp dẫn thẩm mỹ của bảo tàng đã khiến nó trở thành điểm đến phổ biến cho những người yêu thích nghệ thuật. |

| 119 | In times of crisis, people may act out of ………………………………………………………… rather than hope. | Trong thời điểm khủng hoảng, mọi người có thể hành động vì tuyệt vọng hơn là hy vọng. |

| 120 | Unable to withstand the pressure, the old bridge finally …………………………………………………………. | Không chịu nổi áp lực, cây cầu cũ cuối cùng sụp đổ. |

| 121 | ………………………………………………………… can drive people to act in ways that are harmful to themselves and others. | Lòng tham có thể khiến con người hành động theo những cách có hại cho bản thân và người khác. |

| 122 | Knowing the time was short, she ………………………………………………………… the last part of the race. | Biết thời gian không còn nhiều, cô ấy tăng tốc ở phần cuối của cuộc đua. |

| 123 | People’s ………………………………………………………… often guide their decisions and actions in life. | Giá trị của con người thường hướng dẫn các quyết định và hành động của họ trong cuộc sống. |

| 124 | His approach to solving problems is very …………………………………………………………, relying heavily on data and expert opinions. | Cách tiếp cận giải quyết vấn đề của anh ấy rất kỹ trị, dựa nhiều vào dữ liệu và ý kiến chuyên gia. |

| 125 | The village ………………………………………………………… agreed to the terms of the peace treaty. | Trưởng làng đã đồng ý với các điều khoản của hiệp ước hòa bình. |

| 126 | The gap between rich and poor highlights the issue of ………………………………………………………… in our society. | Khoảng cách giàu nghèo nêu bật vấn đề bất bình đẳng trong xã hội chúng ta. |

| 127 | The ………………………………………………………… of the area includes rolling hills, lush forests, and picturesque lakes. | Cảnh quan của khu vực bao gồm những ngọn đồi nhấp nhô, những khu rừng tươi tốt và những hồ nước đẹp như tranh vẽ. |

| 128 | Unlike …………………………………………………………, the social sciences deal with human behavior and societies. | Không giống như khoa học vật lý, khoa học xã hội đề cập đến hành vi và xã hội của con người. |

| 129 | A ………………………………………………………… utility-style job market for irregular labor could help address some of the current inequalities in the workforce. | Một thị trường việc làm theo kiểu công ích công cộng dành cho lao động không thường xuyên có thể giúp giải quyết một số bất bình đẳng hiện nay trong lực lượng lao động. |

| 130 | Seeing the suffering in the disaster-struck area, she felt deep ………………………………………………………… for the victims. | Nhìn thấy sự đau khổ ở vùng bị thiên tai, cô cảm thấy vô cùng thương xót cho các nạn nhân. |

| 131 | Spending money recklessly can be considered a ………………………………………………………… habit, especially in a society advocating for sustainability. | Tiêu tiền một cách liều lĩnh có thể bị coi là một thói quen phung phí, đặc biệt trong một xã hội ủng hộ sự bền vững. |

| 132 | The art critic’s ………………………………………………………… of the new exhibit was not as favorable as the artist had hoped. | Phê bình của nhà phê bình nghệ thuật về cuộc triển lãm mới không thuận lợi như người nghệ sĩ đã mong đợi. |

| 133 | The country’s ………………………………………………………… was evident in its modern infrastructure and high standard of living. | Sự thịnh vượng của đất nước được thể hiện rõ ở cơ sở hạ tầng hiện đại và mức sống cao. |

ĐÁP ÁN

- He has a morbidity fascination with the darker aspects of human history, which some find unsettling.

- In , Keynes addressed a radio audience about the desperate state of the world economy.

- Some cultural traditions are immutable, passed down unchanged through generations.

- Real people are living a vision of the economy as a place of moral action and accountability, rather than a value-free zone of unalterable laws.

- His optimism about the future was infectious, making everyone around him feel hopeful.

- Artists often use a specific pattern in their work to make it recognizable.

- Acts of kindness and virtuous are highly valued in many cultures.

- In , in a book titled “The Slavery of Our Times,” Tolstoy struck some of the same notes about the predictive power of economic systems.

- Investing in the stock market without research is a doomed endeavor; it’s likely to result in significant losses.

- Owning a rural estate is a dream for many who wish to escape the hustle and bustle of city life.

- The plain of Mongolia is known for its vast, open spaces.

- Mainstream opinions are often considered safe and widely accepted in society.

- The consequences of our actions are inescapably; we cannot avoid them no matter how hard we try.

- For his journey across the desert, he planned to cover a distance of miles.

- The arrival of the storm was inevitable, given the weather forecasts.

- And yet, some economists, reviving the attitudes of Keynes and Tolstoy, have appeared more open to the idea that economics is a branch of philosophy.

- It’s important to distinguish between facts and opinions when researching.

- Every action has its consequences, whether they are intended or not.

- The principle of equality lie at the heart of the discipline of democratic societies.

- It’s possible to imagine a future in which economic systems that fail to reflect the true price of goods are seen as uncontroversially wrong.

- Excited about the adventure ahead, the group sets out at dawn.

- The theory was based on quasi-scientific evidence, which made it difficult to prove scientifically.

- His comment was deemed irrelevant to the discussion, as it did not contribute to the main topic.

- True insights about oneself often come from moments of quiet reflection and introspection.

- The judge is known for being just and fair in all his rulings.

- The goal of these initiatives is to decrease wealth inequality and promote a more sustainable economy.

- Being unencumbered by financial debt allowed her to pursue her passion without worry.

- The project’s success was premature; it happened much sooner than anyone expected.

- Behavioral economists focus on how people actually make decisions, including the irrational ways we often behave.

- Despite the misfortune, she kept a positive attitude and continued to work towards her goals.

- An economist studies the economic behaviors and trends to predict future market movements.

- He sold the apartment at a profit, earning much more than its original purchase price.

- To perceive something is to become aware of it through careful observation or consideration.

- The heist was calculated, with every step carefully considered to avoid detection.

- With every beat, his heart hammers like a drum in his chest.

- After years of hard work, she finally became a landowner with vast lands.

- The steppe is characterized by large, grassy areas with few trees.

- Initiatives such as participatory budgeting and climate budgeting are examples of economic reforms aimed at creating a more equitable society.

- And yet it’s possible to marry economics and morality by adopting economic models that give tangible reality to the idea that a better world is possible.

- A moral person considers the impact of their actions on others and strives to do what is right.

- The earthquake was a catastrophe that left the city in ruins and thousands without homes.

- He could not grasp the concept no matter how many times it was explained.

- The corporate concentration in the tech industry raises concerns about market fairness and competition.

- A true statesman is not only a politician but also a visionary leader who cares for the nation’s welfare.

- Their new business venture aims to revolutionize how we use renewable energy.

- Education is a means to a better life, offering opportunities for growth and development.

- He went on, “But after so many failed prophecies, is it not in the interest of social science to embrace complexity, be it at some sacrifice of its claim to power?”

- In medieval times, peasants worked the land to earn their living, often under harsh conditions.

- The dubious nature of the rumor raised questions about its truth.

- Pollution is an example of externalities that affects individuals who are not directly involved in its production.

- Many fairy tales warn about making deals with the Devil.

- The accident deformed his car, making it unrecognizable.

- Thomas Piketty has described economics as a branch of political philosophy.

- We must shift our notion of the economy from an impersonal sphere of abstract forces into a human arena of ethical decisions.

- Decisions should be made rationally to avoid unnecessary risks and consequences.

- The fertile valley was ideal for growing a variety of crops.

- The town of Mondragón is home to the world’s largest integrated network of worker and multi-stakeholder coöperatives.

- The economist Albert Hirschman suggested that those at the top of society often seek to impress the general public by proclaiming that their status is the “inevitable outcome of current processes.”

- She was amazed by the minuscule detail of the miniature painting.

- The prospects for the new technology seemed promising, attracting many investors.

- In an individualistic society, people prioritize their own goals over the collective good.

- The dimension of an argument can include various perspectives such as emotional, logical, and ethical aspects.

- The issue was somewhat complicated, more than initially thought.

- Political interference can sometimes hinder the progress of important legislation.

- They may see current corporate ownership models that permit extraordinary concentrations of power and wealth as absurd.

- Falling for the sunk-cost fallacy means continuing a project just because you’ve already invested a lot in it, not because it’s the best decision going forward.

- Challenging the status quo often requires courage and innovation.

- “At the end of the eighteenth century, the people of Europe began little by little to understand that what had seemed a natural and inevitable form of economic life was unjust.”

- They recognized that the position of peasants who were completely in the power of their lords was not only wrong but also immoral and demanded change.

- Tolstoy’s approach, focusing mostly on moral and spiritual reforms, isn’t likely to strike us as appealing today.

- Despite his achievements, he remained humble, always giving credit to his team.

- Less dogmatic economics education could open the door to more diverse and innovative economic thinking.

- The decadent lifestyle of the early th century led to significant social and moral changes.

- They enjoyed a leisurely stroll through the park, appreciating every moment of the sunny day.

- As the sun dipped towards the horizon, they realized they needed to find shelter quickly.

- “We have, all of us, mismanaged our affairs,” Keynes said, highlighting the need for a new approach to economic management.

- The military decided to deploy new strategies to improve defense mechanisms.

- The whole affair involved complex negotiations and delicate diplomacy.

- People usually grow accustomed to the climate of the place they live in after a while.

- After running the marathon, he was completely exhausted and couldn’t take another step.

- Engaging in self-destructive behaviors can be a sign of underlying issues that need to be addressed.

- The festival winds to a close, signaling the end of summer and the beginning of fall.

- After the marathon, she was overwhelmed by fatigue and could barely stand.

- She decided to pursue her dreams at all costs, no matter the obstacles she might face.

- The hedonic treadmill suggests that our pursuit of happiness often leads us back to our starting point, no matter what we achieve.

- The obnoxious smell from the kitchen made it hard to stay in the apartment.

- Studying this discipline requires dedication and an analytical mind.

- The athlete had to forfeit his title after being found guilty of doping.

- The event planner managed to orchestrate a perfect wedding ceremony despite the challenges.

- The national park is one of the largest tracts of untouched wilderness in the region.

- His muscles were aching after the intense workout session.

- The committee strives for impartiality in evaluating all applications, ensuring no bias.

- After receiving the good news, she felt completely content.

- The research project will culminate in a comprehensive report detailing our findings over the past year.

- The policy changes obscures the true impact on the community, making it hard for citizens to understand.

- Making ethical decisions is crucial for leaders to maintain trust and integrity.

- People often find the disgusting of waste in food production to be a major ethical issue.

- Falling off his bike, his knee was bruised but not seriously injured.

- Neighbors often quarrel with over boundary lines that are not clearly defined.

- The knight embarked on a quest to find the lost treasure, facing many challenges along the way.

- The startup became prosperous within a few years, attracting significant investment.

- Good reasoning is essential when solving complex problems.

- She viewed her extensive book collection not just as possession but as gateways to different worlds.

- Wow! he exclaims, impressed by the magician’s trick.

- Resources are limited on this planet, making conservation and sustainable use essential.

- The detective worked relentlessly to solve the mystery, leaving no stone unturned.

- The main character in a novel is often referred to as the protagonist.

- Despite his wealth, he remained dissatisfied with his life, always wanting more.

- The field of psychology explores how individuals think, feel, and behave in different situations.

- The movie was perceived as a masterpiece by critics, despite its initial mixed reception.

- Economic thinking is crucial when making decisions to ensure they are beneficial in the long term.

- In today’s consumer society, being acquisitive is often seen as a virtue, but it can lead to negative consequences.

- Caught in the rain, they were soaked to the skin by the time they reached home.

- A healthy public discourse is essential for a functioning democracy.

- Climbing Mount Everest is a challenge to many mountaineers, testing their skill, endurance, and willpower.

- He was tempted by the thought of discovering hidden treasures.

- Smugglers often smuggle illegal goods into the country, bypassing customs.

- The museum’s aesthetic appeal made it a popular destination for art lovers.

- In times of crisis, people may act out of desperation rather than hope.

- Unable to withstand the pressure, the old bridge finally collapses.

- Greed can drive people to act in ways that are harmful to themselves and others.

- Knowing the time was short, she charges up the last part of the race.

- People’s values often guide their decisions and actions in life.

- His approach to solving problems is very technocratic, relying heavily on data and expert opinions.

- The village chief agreed to the terms of the peace treaty.

- The gap between rich and poor highlights the issue of inequality in our society.

- The landscape of the area includes rolling hills, lush forests, and picturesque lakes.

- Unlike physical sciences, the social sciences deal with human behavior and societies.

- A public utility-style job market for irregular labor could help address some of the current inequalities in the workforce.

- Seeing the suffering in the disaster-struck area, she felt deep pity for the victims.

- Spending money recklessly can be considered a profligate habit, especially in a society advocating for sustainability.

- The art critic’s critiquing of the new exhibit was not as favorable as the artist had hoped.

- The country’s prosperity was evident in its modern infrastructure and high standard of living.

MỘT BÀI HỌC KINH TẾ TỪ TOLSTOY

Vào năm 1886, nhà văn người Nga Lev Tolstoy đã cho ra mắt một truyện ngắn mang tên “Người ta cần bao nhiêu đất đai?”. Câu chuyện kể về Pahóm, một nông dân nghèo khổ, luôn ấp ủ giấc mơ trở thành chủ nhân của những mảnh đất rộng lớn. Pahóm từng nghĩ, “Miễn là tôi có đủ đất, dù cho ma quỷ đến cũng không sợ!” Lời nói ấy vô tình lọt vào tai quỷ dữ, và nó quyết định sẽ khiến Pahóm phải trả giá.

Tolstoy không phải là một nhà kinh tế; thực tế, ông đã tiêu xài hoang phí đến mức một lần đã mất trắng gia sản ở nông thôn trong ván bạc. Tuy nhiên, câu chuyện “Người ta cần bao nhiêu đất?” lại mở ra nhiều cái nhìn sâu sắc về tiền bạc, tâm lý và tư duy kinh tế.

Minh họa bởi Simon Bailly

Vào năm 1886, nhà văn người Nga Lev Tolstoy đã cho ra mắt một truyện ngắn mang tên “Người ta cần bao nhiêu đất đai?”. Câu chuyện kể về Pahóm, một nông dân nghèo khổ, luôn ấp ủ giấc mơ trở thành chủ nhân của những mảnh đất rộng lớn. Pahóm từng nghĩ, “Miễn là tôi có đủ đất, dù cho ma quỷ đến cũng không sợ!” Lời nói ấy vô tình lọt vào tai quỷ dữ, và nó quyết định sẽ khiến Pahóm phải trả giá.

Khởi đầu bằng việc vay mượn tiền bạc để mua đất, Pahóm bắt đầu con đường làm giàu của mình bằng cách chăn nuôi và trồng trọt. Thời gian sau, nhờ bán đi những thửa đất mình có được với giá cao, anh chuyển tới một nơi mới, nơi mà việc mua bán đất đai trở nên dễ dàng hơn bao giờ hết. Một thời gian, Pahóm tưởng như mình đã tìm thấy hạnh phúc, nhưng rồi, sự giàu có mới mẻ này cũng không làm anh thỏa mãn. Anh vẫn phải thuê thêm đất để trồng lúa mì và thường xuyên xảy ra tranh chấp với những người nghèo khổ hơn về quyền sử dụng đất đai. Pahóm tin rằng, chỉ cần sở hữu nhiều đất hơn nữa, mọi vấn đề sẽ được giải quyết.